Il Poggio di San Remo

The finale of Milan-San Remo kicks off with one of the great arm wrestles of cycling, on one of the many hills of the Mediterranean coast. It's called Il Poggio di San Remo.

There are thousands of Poggios in Italy, because poggio means knoll. The dictionary says it’s a small hill or mound, nothing more. The Poggio di San Remo is a jewel, although only because of its setting. Its statistics are insignificant, it isn’t long or high or steep. The road up it is narrow but quite well surfaced. Even the curves of its descent only catch out those who run out of luck or talent. It’s just another hill at the back of a town on the Ligurian coast, with nothing more spectacular than a wide blue Mediterranean view. Or it would be if it wasn’t for La Classissima, the classic of classic as some Italians call Milan-San Remo.

It’s the first of the five ‘monuments’ each year, and some riders, fans and media think it’s the best. Its history is long, the athleticism of its winners cannot be denied, the race route is special, and Il Poggio di San Remo, with a descent that tumbles into the streets of the finish town itself, is its final climb.

The long wait of winter, the passion of the Tifosi, the ambition of the world’s best bike racers, they collide on the slopes of Il Poggio. And when they do they produce some of the most charged moments in bike racing. That’s what makes Il Poggio di San Remo special; not gradient or number but anticipation, hope and history.

Il Poggio on race day

You can cut the atmosphere with a knife on race day, especially in recent years. In the past when gaps in talent, motivation and money in pro racing were bigger, Milan-San Remo had winners who went from a long way out, either on their own or in small groups. That doesn’t happen now, even though the organisers have persistently toughened the route, which is why they included Il Poggio in the first place.

Its first appearance was in 1960 when someone hit on the idea that including a climb eight kilometres from the finish would prevent the sprints that increasingly decided Milan-San Remo. It’s a fact of cycling history that sprinters used to get a bad deal. Fans, the press and race organisers somehow thought that they won through craft, and that the only victories worthy of great races were lone ones, especially long heroic lone ones

The greatest of Milan-San Remo’s lone winners, Fausto Coppi, who died only weeks before the 1960 race, was remembered with a minute’s silence before the start in 1960. And Coppi’s memory was served well when the Frenchman, Rene Privat launched a solo attack on the Poggio to leave the remnants of the day’s leading break, and frustrate the efforts of Rik Van Looy’s ‘Red Guard’ Faema team, who were chasing it.

Fausto Coppi

Raymond Poulidor won alone in 1961, as did a tiny Belgian called Emile Daems in 1962. Then the Poggio saw an epic duel between Poulidor and Tom Simpson in 1964. The two hit the climb together with a good lead, and almost immediately Poulidor attacked. Simpson hauled him back, only for the Frenchman to go again. And so they continued all the way to the top, by which time Poulidor had fired all his shots and Simpson was still with him. The sprint on the Via Roma was a formality for the Englishman’s second monument.

Poulidor winning in 1961

And so the story continued. Eddy Merckx made the Poggio his own by winning seven times in San Remo. Michele Dancelli punctuated Merckx’s run with a brilliant solo victory, restoring Italian pride in 1970. Then in 1974 we saw one of the best ever editions of Milan-San Remo.

Eddy Merckx, seven times a winner

Of all his rivals Eddy Merckx singles out Felice Gimondi as the man he respected the most. “He was like me in many ways, we had the same strengths, but above all I knew that Gimondi played everything straight. That’s why when he beat me, and he did so several times when I was at my best, I had no excuse,” Merckx says.

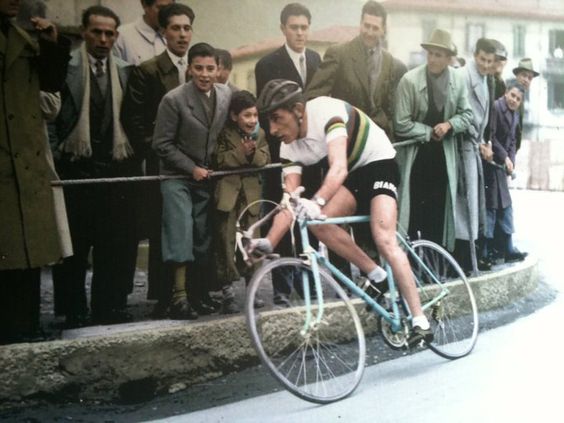

Merckx’s reverence adds a sheen to Gimondi’s stature, and it’s one reason why Gimondi’s 1974 San Remo victory is remembered so fondly. He beat Merckx, who by then had won in 1966, ’67, ’69, 71 and 72, and would win again in 1975 and 1976, so he beat Merckx at his best. But there’s more. Gimondi won on a Bianchi bike, Coppi’s bike, the bike that has the longest history with Milan-San Remo, and he won while wearing the rainbow jersey. That jersey, the celeste bike, Gimondi pounding over the Poggio, alone in the spring sunshine, it's one of the iconic moments of this iconic climb.

Gimondi in 1974

But as the years went by Milan-San Remo victories became less clear cut. Bigger groups were left at the end, sometimes even the whole field. So more climbs were added; La Cipressa in 1982 and La Manie in 2010 are the two best known. They beef up a course that includes a serious climb of the 532-metre Turchino pass at 142 kilometres, and the three Capi; the Mele, Cervo and Berta, strung out along the coast road, the ancient Via Augusta built in 1 AD under the rule of Emperor Julius Ceasar. Still, increasingly, all these hills do is act as a lens focusing the race on to Poggio.

Riding the Via Augusta

On any other day Il Poggio di San Remo is insignificant, a drab suburban road in the hills, dotted with houses and lined with acres of poly tunnel for growing early fruit. The climb starts at a jumble of road signs indicating a right slip off the Strada Statale 1. The gradient changes from the main road’s slightly downward trend to upwards, but not by much until the first right-hand bend.

This is where the first attacks go; either team plans to soften up rival sprinters, or chancers who want nothing more than make their name. They spring from the peloton and fizz upwards like penny rockets, before falling to earth and are gobbled up by the hungry peloton. Up the road goes through left and right bends, the sea on one side and solid rock or boulder walls on the other, then it descends in the same manner.

First attacks on the Poggio

And that’s all there is to is, a wriggle of road clambering over a knoll. The Poggio di San Remo only works on race day, to go there on any other is underwhelming. It’s not like other iconic places. The great mountain passes have their spectacular views. Climbs like the Muur and the Koppenberg, or stretches of cobblestones like Arenberg, are a test to ride on any day. The Poggio isn’t, unless you count dodging the huge dustbins that line the road. The Poggio is like an empty velodrome, it needs a race to make it work.

The steepest gradient comes just before a green-painted house on the inside of a sharp left bend. Then the last quarter of the Poggio begins, and sprinters start believing they can be there at the end. There's one more steep bit, not much steeper but enough for a climber to attack. If he's really good, and totally commits, he might succeed.

More left and right bends, up past the cylindrical concrete irrigation ponds that feed the farms. Then the gradient lessens and the mood changes. The sprinters know they can be there now. The summit comes quickly, and rag-tag farms are replaced by the smart houses of Poggio di San Remo village. The last gambit is an attack across the top and a reckless descent. It’s worked in the past, and will work again.

More than any other climb going down the Poggio is as important as going up. It’s just as crucial, just as tactical. No one can relax, unless they have given up the fight. If a powerful rider gets a gap on the descent it’s hard to close in 2.9 kilometres of flat to the finish line.

Roger De Vlaeminck wins on the Via Roma

The descent was the last throw of the dice when, for few a years, the race finished on the Corso Cavalotti, like it did when Sean Kelly won a second time in 1992. The longest serving finish, on the Via Roma, favours any sprinters left in contention. But Il Poggio is still the place to be on race day.

Locals come out of their houses carrying TVs with metres of cable attached to watch the race before it arrives. The atmosphere builds slowly but is at fever pitch when the riders arrive. They hit the climb like multi-coloured waves crashing against a rocky shore, giving every scrap of energy left after more than 280 kilometres in the saddle. Attack, counter, bridge, race! That’s the spirit of Il Poggio di San Remo.