In March 1971 a short but incredible cycling career that promised so much, and the life of a very special person was lost in a freak accident.

Some people fizz like fireworks, delight all they touch, and are gone. Jean-Pierre Monseré, known as ‘Jempi’ to friends and fans alike, was one of them. He was a brilliant bike racer, colourful in life, a born entertainer but Monseré had one full year as a pro then died in a racing accident. It was tragic, and his family suffered again four years later when his son Giovanni was killed on the road, doubling their loss.

What could have been? Even Eddy Merckx didn’t have a pro debut like Monseré’s, and it was better than Remco Evenepoel’s last year. Monseré was born in 1948, two and a half years after Merckx; they were rivals. Would Eddy’s career have been so great had Monseré lived? He was a threat in any classic, he’d already proved that.

He was born in Roeselare, West Flanders; the same as Patrick Sercu, where young boys were surrounded by bikes. There’s a long tradition of racing in this part of Belgium, and all Jempi ever wanted to be was a pro bike racer. By 13 he was winning, and he progressed through the junior and amateur ranks adding 20 to 30 races a year to a glittering palmarès.

At the age of 20 Monseré took the silver medal in the 1969 amateur road race world championships in the Czech Republic. He became a professional rider on September 1st that year, joining the Flandria team. It was the start of a busy few weeks. Monseré celebrated his 21st birthday on September 8th, won his first pro road race a few days later at Kokelare, then on October 11th he won Il Lombardia, outsprinting an eight-man break in Como. Six weeks a pro and he’d won his first monument.

The winner of Il Lombardia 1969 is third in line in the winning break. Herman Van Springel leads with Felice Gimondi following.

The winner of Il Lombardia 1969 is third in line in the winning break. Herman Van Springel leads with Felice Gimondi following.

It was sensational, but Jempi was just as sensational in his private life. He loved parties and was great company earning a reputation as a playboy. But that was all it was, a reputation, even if he went to enormous lengths to preserve it.

Freddy Maertens was close to Monseré, their wives are cousins; he remembers Monseré and really looked up to him. “He liked to play tricks and he liked to make people think he wasn’t serious, that he didn’t even train. It wasn’t true, because if you went training with him he would kill you. He rode very hard, like everything he did his training was full on. Sometimes in summer he would go out at 6am, returning at nine to change back into his dressing gown. When the guys he arranged to go training with that day arrived he would tell them he didn’t feel like it, but as soon as they left he was out again for another two hours behind a Derny.”

Freddy Maertens

Freddy Maertens

Monseré was serious, he was talented and he had the drive to make it really big. The World Championships in 1970 were in Leicestershire on a course criticised by some, particularly by Eddy Merckx, for being too easy. Merckx was doubly fed up because the previous year the worlds were in Belgium and he was flying, but the road race course was a soft one there as well. Monseré saw Merckx’s indifference as an opportunity, he raced and trained with one objective for 1970; the rainbow jersey.

After doing well in the classics, with top-ten placings in Flanders, Ghent-Wevelgem, Flèche Wallonne and Paris-Roubaix, he swerved the Tour de France and started preparing for the worlds in the time-honoured Flanders way. The same way his mentor Briek Schotte prepared when he won his world titles in 1948 and 1950. All through July and August Monseré rode kermesse races, three or four a week, and he rode to them and back home after, often getting 250-plus kilometres in his legs. He didn’t take the races easy either, adding several to his total of 17 victories in 1970. By the championships he was flying.

Since Merckx made his feelings about the circuit very plain Frans Verbeek, who had won 20 races that year, was the Belgian favourite. The Belgian team was happy for Monseré to go with every break, which suited him because he ended up in the big one that shaped the race.

Frans Verbeek (left) with Eddy Merckx

Frans Verbeek (left) with Eddy Merckx

The Italian team was lively from the start and eventually got a move going with their best three riders; Gianni Motta, Michele Dancelli and Felice Gimondi in it. But they were too good to be given much leeway, so the rest of the peloton chased, but just as they were being caught Gimondi attacked gaian, this time with a Frenchman, Alain Vasseur. Monseré chased and caught them, so did the Dane, Lief Mortensen and a brilliant Brit called Les West.

Felice Gimondi

Felice Gimondi

They cooperated, and the break stuck. Monseré had been out front most of the day, like Gimondi, but the young Belgian was cannier with his effort. With the world title just up the road now though, he committed everything to the break, then put his head into winning.

He attacked with about three kilometres to go to, but it was a test. He noticed that Gimondi reacted first and strongest, so he said later that when he really went he made sure the Italian was nowhere near him. He saw his moment with one kilometre to go and went, but properly now. The others could do nothing. Mortensen finished second, Gimondi was third and Les West fourth. A superb win for the Belgian, and a brilliant performance from the British-based West.

Les West, British star of the 1970s, still riding in his 70s

Les West, British star of the 1970s, still riding in his 70s

Monseré was now the man, eclipsing even Merckx in Belgium. What did the future hold? He spent a serious winter, enjoying the receptions he went to but knowing when to leave. He won the Ghent Six-Day with Patrick Sercu, and was in fine form from the following February when he won the Tour of Andalucia.

His first major objective for 1971 was Milan-Sanremo. Briek Schotte convinced the new world champion to adopt his old-fashioned training methods again; long miles in the Flanders rain, rather that too many races in the south. And although Schotte was 56 years old he was still very fit, he trained with his protégé from time to time. Knowledge gained on those rides and his Andalucia result convinced Schotte that Monseré didn’t need another big stage race, so Paris-Nice was missed in favour of a long weekend of single-day races in Belgium as his final preparation for ‘La Primavera’

On the Saturday Monseré was second to his great friend and kindred spirit Roger de Vlaeminck, then ninth the next day. One more kermesse in the little village of Retie near Antwerp, then Monseré would leave for Milan. That was when disaster struck.

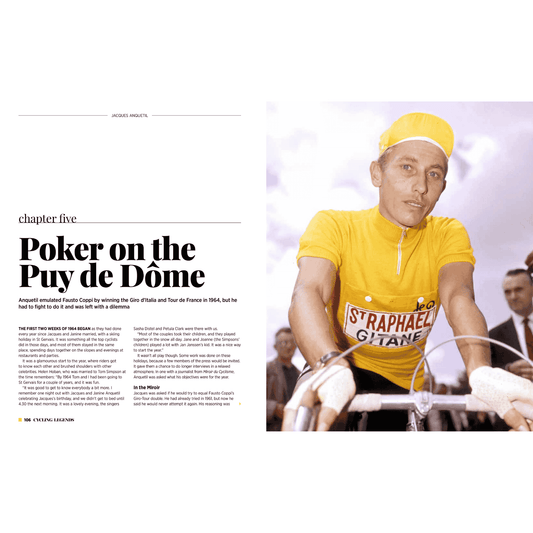

The 1970 pro worlds in Leicester

The 1970 pro worlds in Leicester

Seventy-one kilometres into the race a break of 15 was strung across the road in an echelon. Monseré had just done his turn at the front, and was settling at the back of the string in the left-hand gutter. Somehow a car had got the course and was heading towards them. It happened so fast, the roads were closed so nobody expected it. Raf Hooyberghs, who was just in front of Monseré, saw the car at the last second, swerved and missed it. Monseré didn’t. He hit the car head-on and died instantly.

The cycling world was turned upside down. Frans Verbeeck, who was in that break, says he still remembers the noise of that crash. Roger de Vlaeminck, a rider so close to Monseré, travelled to the race with his friend and remembers; “It was terrible. I had to take his car back home, but I was in a daze. I couldn’t believe it. In fact it took me a long time to accept it.”

Jean-Pierre Monseré

Jean-Pierre Monseré

A great talent and a great person had gone. And with tragedy knowing no bounds the Monseré family was struck again a few years later when Jempi’s seven year-old son, Giovanni was killed when a car hit him while out riding his bike. The bike was given to him by Freddy Maertens, a Flandria bike just like his father rode. It happened in 1976 while the Tour de France was on, and Maertens was winning stages and in the green jersey. There were several days to go, but nobody told Freddy because they knew he would leave the race. They were right, he was devastated when he was told on the final stage. He still is...

The Grote Prijs Monseré celebrates his memory today

The Grote Prijs Monseré celebrates his memory today

1 comment

Yes, I was at Mallory Park that day Monsere became World Champion—a tough enough race with the four best riders contesting the sprint.

A terrible loss to cycling.