Cycling Legends interviews are sponsored by:

The Cycling Entrepreneur

Part two of our interview with Phil Griffiths, the man who brought Assos and Pinarello to the UK and created ANC-Halfords, the first British trade-sponsored team to take part in the Tour de France. And he's is still a force to be reckoned with in the bike business today.

Words: Chris Sidwells

Photos: Andy Jones and Cycling Legends

Q: You’ve become close to many of the riders you sponsored, it seems they are more than just part of business deals for you, is that true?

“I could have become a rider’s agent or a contracts manager. When Teka was interested in signing Malcolm Elliott, I told them they could have him for 180 grand. But Malcolm was young and he took an established rider’s agent to the meeting with him, not me. Well he got there and Teka said, “Where’s Phil?” Then Malcolm’s agents says; “I believe you’ve got an offer for us.” And they said, “Yes, 150 grand.” So Malcolm says; “I thought it was more.” But Teka says, “Yes, but we don’t pay him,” meaning the agent, that comes out of the rider's money. I told Malc afterwards that he wouldn’t have had to pay that with me. It took Malcolm a while to catch on to how they did deals in cycling.

“The other thing Malcolm learned with Teka was they didn’t pay him direct. There was a go-between, a sports promoter who had an office above a gymnasium. Malcolm said to me one day after ANC, when he was with Teka, he said he wanted to go down and see Teka, see the whites of their eyes. I said Malc, you’ve got to go to a gymnasium. You don’t go to Teka, you go to see the middle-man.

Malcolm Elliott

“Then Malc is ringing me from the Tour of Spain, which was earlier in the year back then, and he says; “I’m not starting tomorrow, I’ve not been paid by Teka for three months.” And I go; Malc, you need to speak to the middle-man, he’s making a precentage on your money, and all the riders’ money, by leaving it in his bank account, that’s another earner for him. But don’t leave the Tour of Spain, what you going to do when he pays you next week? You can’t come back to the Tour of Spain and start again.” But you see what I should have been doing, I should have been on the plane alongside Malc so he didn’t have the meltdown.

Q: Malcolm Elliott was part of the ANC team, the first British trade sponsored team to ride the Tour de France. The only one before Team Sky. Can you give the readers some insight into how that team was formed?

“It was 1986 when we got Tony Capper, the boss of ANC, really hooked. Micky Morrison got Capper down to a big race on the Isle of Wight. Anyway he saw the race, loved it, and he saw the following cars and all the motorbikes zooming by after it, and the crowds that turned out, and he loved it all. So he comes to me and says, “What do you reckon to this Tour de France, why can’t we do that?” So I explained it was another level, and he says; “Okay, take me to see a stage.”

“I said ok, I’ve got to book some things. I went away and booked hotels and stuff and I drove him across to the Tour in a V12 Jag XJS. He thought I was trying to kill him. So Capper saw the Tour, saw how big it was and said; “We’ll come back next year.”

The 1987 Tour de France peloton with the first ever UK trade team in it.

“When he said it, I didn’t realise what he’d said, it didn’t sink in. I thought he meant we’d come and watch it next year, have another trip, a little holiday, but he meant we’d come back as a team and ride it. So next thing is we go back home and he’s straight on to ASO, saying what have I got to do to get a team in the Tour De France? And they told him “You’ve got to ride everything, the classics, even Bordeaux-Paris. You’ve got to ride Paris-Nice, you’ve got to ride this and you’ve got to ride that.”

“And now, when I read what they write about ANC, that we weren’t prepared for the Tour, it’s not true. We rode everything before, and we had some good riders, and when the lads all went well, ANC was a good team, but I still I don’t know how we got to the Tour. We hadn’t trained like the Europeans pre-season, but we still went to everything; every race. We were there at the Tour of the Mediterranean, we were there at Paris-Nice. Nigel Bloor even took on Bordeaux-Paris. He wasn’t ready for that, we just sent him to be there so we could say to the Tour de France organisers; “Yes, we did that, we were there. We rode Bordeaux-Paris”

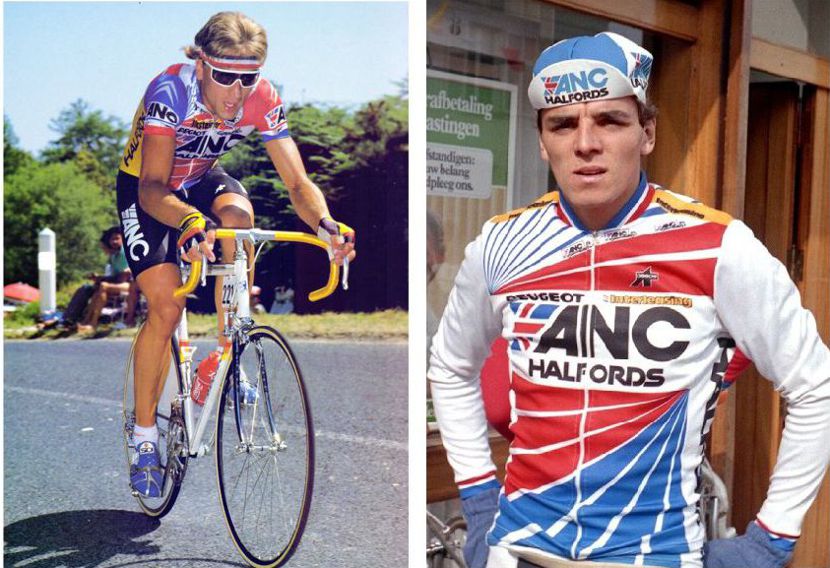

Two of ANC's best, Malcolm Elliott and Joey McLoughlin

“Capper tried to sign Phil Anderson, but Phil always pushed the boat out a bit. He wanted his salary, but then he wanted plane tickets to America, his wife was American, as well as other stuff, and all on top of what he got paid. Then Capper said; “I want Kelly, I want Roche.” And I told him I’d start asking. So I starts asking around because none of them had got long-term contracts. But there was an unwritten law we stumbled across when I was talking to Teka about Malcolm. You couldn’t touch Kelly while he was with Kas, there was an agreement between the teams not approach him, but when the old man Knorr died, the boss of Kas (the Spanish drinks company), the agreement ended. The guys with Spanish teams were all taking chances on whether they were going to get paid back then, so Kelly went with PDM because it was new and it was Dutch.

Q: When you look back on your life in cycling, and especially in the business of cycling, you have had many highs. That’s obvious from your enthusiasm and from what you have achieved, but have there been any low points?

“What do I say here? No, no lows really. I had some sticky moments, especially taking something big on when I’m thinking ‘how am I going to do this?’ But no lows. I remember a saying I heard as a kid; ‘it’s better to burn out than fade away’ so I went for burn-out, but to be honest I wouldn’t mind a bit of fade now, I’m still too busy.

“Basically I’ve made money because I can strike up relationships. Like I did right at the start with Toni Maier. We had lots of experiences together. I like driving through the night, so one time I drove to Calais, and drove thought the night to see Toni in Switzerland. I did it just because it was his birthday. I got to his place and I went; Toni it’s your birthday. Happy Birthday, where do you want to go?

“And he says; “Menton, I want to go to Menton.” I’ve just driven a thousand miles and he wants to go to f***ing Menton in the South of France. So I said; Yeah, yeah, hop in. And off we went to Menton.

We called in on Phil Edwards, who lived down there. He lived there and ran a bike business in Roquebrune, right up in the sky in this grotto. We get there, and it’s closed on a Wednesday. So I’d driven through the night to Switzerland, then straightaway got back in the car and I’d driven to the South of France, thinking I can have a rest at Phil’s. And we get there and Phil’s place is shut, no sign of him, so I’m sobbing like a dog in the Peace Race. But I’m used to it, I can put up with it.

Phil Griffiths putting on the Peace Race leader's jersey

“I had some mates from Gloucester where I come from, who I started cycling with, and they used to win, they were the best riders. Tell you what though, they used to say I could suffer like a dog, and I’ve been like that in business, I’ve worked and worked like a dog. I had some good examples though.

“I remember when Reg Harris was offered a job by Draka Foam way back in the 1960s, they said to him, “You can have 25 grand and a big fancy Ford car, top of the range.” And he goes; “Well, is there another option?” And they said; “Yeah, you don’t get anything, you don’t get a salary you just get ten percent of what you sell.” So he said “Let me have a look at the contract, I’ll get my lawyer to look at it.”

“Next day Reg came back and said; “Ok, I’ll have this one, the one where you just pay me ten percent of what I sell.” Nobody had ever asked Draka Foam for that, so they went for it, and by the end of the first year, and this is in the 1960s remember, Reg had made 75 thousand and bought himself a Ferrari Dino.

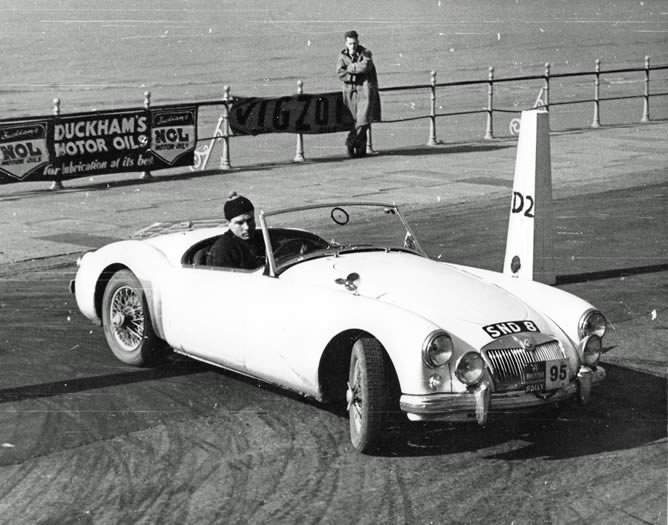

Reg Harris loved fast cars and had several goes at motor racing

“Reg was an example. When he came back in the 1970s I used to pick him up for training, and one day he said to me; “You know, with all these hours you’re doing on the bike, if you do that in a business it will be just as successful.

“And Tony Capper from ANC was another example, he had vision. All his accountants told him he’d get two, three or maybe four percent growth in parcels delivery, but he was going for eighty percent growth, and he was right. He set up ANC as a hub, then sold the name as a franchise. Chris’s Deliveries in Worksop, or wherever, would be ANC Worksop, and Jock’s Transport in Glasgow would be ANC Glasgow. He wanted to put his hub in Luxembourg, then get all the transport and distribution in Europe. He was way ahead of his time. I just bounced off him.”

Q: Is the secret of success in business to think big?

“No, it’s not artificially to do something, it just comes; you get a knack. You look at a frame, you look at clothing and you think they will sell, and you go for it. Take this example; Freddy Maertens was doing Assos in Belgium when I was doing it in Britain. But one day Toni Maier says to me; “Freddy has to have sold the shorts before he orders them. It was the same in the Tour de France, you don’t sprint till you see the line. You don’t order something until it’s sold. But now we have the 100-mile English time trial champion, and he orders everything in thousands; one thousand of this, one thousand of that, and everything six months before the first sale.”

Freddy Maertens

“So Tony preferred dealing with me, and I always knew I would sell the stuff because of my relationship with the bike shops. I ended up being part of Assos history because when they ask Toni when the first victories were in Assos kit he always says; “Two time trials in 1978. One by Joop Zoetemelk in Lugano and the other by Phil Griffiths in England.” Because that year I won the national 50-mile title in an Assos skinsuit with GS Strada-Lutz on it.”

Q: And Assos became a big thing with British clubs, the riders took to the brand, it was the kit to have.

“That was the marketing, if you saw Assos at the Tour de France then Hans or Tommi would be there; those two did the marketing for Assos and got the products going. The strongest markets were the USA, the UK and Germany. One year I’d have the biggest figures, another year it might be Germany or the US, because maybe we had foot and mouth going on, or there was the Iraq war. People weren’t getting on the bike and thinking about which hats to buy. Anyway, with foot and mouth all the shops here struggled.

“So looking back on my life now I’ve had highs in business, highs in racing, highs with the teams, it’s all been one long high really. No bad times. I was 70 on March 18th this year, and I’m more frustrated that I can’t do all that I want to do. Not because of age, but I’m really pissed that I couldn’t finish my concept stores for Pinarello. They’re doing a complete 180 now. They’re going back to the trade, back to putting two frames in a shop. What for?

Q: Are concept stores, single-brand stores the best way to go in bike retail now?

“Well, when someone comes in to buy a nine grand Pinarello F10, and that’s all he wants, he knows he wants. But somebody else might want and F10 but think the wife’s going to kill him if I buy a nine grand bike. In a concept store he might take the F8 for six grand instead. Or he, or she, might come in for an F8 and have second thoughts at the price and take a Gan to save a grand. And so on and so on. So whoever walks into a Pinarello concept store to buy spends something on Pinarello.

The Pinarello F10

The Pinarello F10“Now, if they go into a shop that stocks several brands they might have gone in wanting an F10 but been worried about the price, and they see a TREK at two grand cheaper, they buy the TREK. They’re all nice bikes, but from a manufacturer’s point of view it’s the completely wrong way to go.”

“It’s like in a race, if you can’t win then you can make money from helping somebody else win. I’d always help Les, Les West, if I could. After this one race he gave us a tenner, and he goes, “You alright with that?” I said yeah. Then he says, “How much have you took today then?” Er, 85 pounds, I told him. And this was 1970. So Les says; “Hang on, I won the race and I didn’t get that much. How did you get all that? So I told him. I said, well you know when you went up the road with Albert Hitchin? Well Colin Lewis told me he was going to jump after you, and if I didn’t follow him he’d look after me, so he gave me a tenner. And then there’s me and Bob Addy left, and Bob says to me, “You’re not going to sprint me are you?” So I said no, and he gave me something as well, then I got my prize money for fifth place, and you just gave me ten quid. That’s how I made 85 quid.

Les West on a recent ride in Staffordshire

“There was one Star Trophy race on Gun Hill that Bill Nixon gave me. Bill used to give me a couple of races a year. I rode flat out for Bill in GP Liberazione, which he won, and flat out in the Milk Race and the Isle of Man, for Bill again. Those races were of no interest to me. I was still fourth in Liberazione though.

“I used to ride the Manx International like it was a one-lap time trial, one lap of the TT circuit. I’d ride it like a one-lap then hang on (the race was three laps), because I was a time triallist first. There was one year, 1973 I think it was, when I missed the break. It was won by a Swiss climber, and the break went first time going up the mountain. So when we came through the finish at the end of the first lap, I jumped away. It took me 37 and a third miles to get across to the break, one whole lap of the TT circuit, because I was such a tester. I wasn’t like Phil Cheetham or others back then, bean-poles who could get across to a break in five miles or less.

“So that’s my life, basically I’ve gone from one high in racing to another in business. When Pinarello came to me, I suppose they saw what I’d done for Assos and thought hey, come on we need to work together. But by then I’d got money with me, I’d got success, I’d got the contacts. I could see the trade was jumping on too many brands as well.

“So I met Fausto (Pinarello) and he liked me, and we started doing business. We had the brand in shops in the UK, but it wasn’t working, it wasn’t working out, not as I thought it could. So I want to Fausto, he knew I was full of energy, and I said; look, I want to open Pinarello Concept Stores.

Fausto Pinarello (centre)

“So I opened in Regent Street first. I took Fausto there the week before we opened, when it wasn’t quite ready. He was in London to watch Brad’s Hour Record and had brought Miguel Indurain with him. I met him and told him we had to find a taxi, so he says “Where is it, where is the shop?” And I told him, near the Queen’s house, meaning Buckingham Palace. “Ah okay, bravo, bravo,” he says. So we pulled up in Regent Street, and Fausto gets out and looks around at all the big name shops and brands, and he says; “Phil, come on; I want to be a partner in this.” He offered me money, but I said no.

Then on the day we opened the Regent Street store, Lord Sugar came, Bradley’s Jag was outside, and we had all the hype, and Fausto just loved it. He said “You’re the only one in the world; the only concept store, we don’t even have one in Italy. There’s my sister’s little shop in Tokyo, but that’s closed down now.”

“Then, at that time I had people ringing me from Tokyo, from New York saying can I come there and partner a shop with them? I told them they had to ring Fausto, I was in England. It was unbelievable, those stores. Straight away a big success financially. When the current owners of Pinarello took over the brand they needed to buy me out. I could have stayed, there were different choices, but I’d have to stay for five years. I was coming up to 70 and I told them; look, I can double the shops in eighteen months, but I don’t know if I can do five years. My body is not the same now, I can feel the difference. You go back five or ten years and I can feel the difference. My mind’s better than it’s ever been, but the body is starting to fall apart.

“I can walk from home to here in Stone and back, but I’ve not got the same physical capacities as I had. Still, last Sunday I took all my cars, one by one to a car wash I own in Stone, and I cleaned them myself. Top to bottom, really early in the morning, so I’m still quite good. I’m still going, still loving it and still full of enthusiasm.”

And that’s Phil Griffiths today, still full of energy, full of plans for the future, and still in the bike business with his company Yellow Ltd, which distributes Rudy Projects and Giordana. “It’s as good as Assos now I think, but we have to build the profile of Giordana, build the name,” he says. He’s working on a big project in Mallorca, too, but more of that another time on www.cyclinglegends.co.uk . For now though, thanks for a very interesting lunch Phil and for providing an interesting read.

You can read Part 1 by clicking this link.

Malcolm Elliott modelling Rudy Project in his inimitable style