Briek Schotte was a granite link in the DNA running through Flemish cycling, a big winner with a very long career, both as a rider and as a team manager.

Words and photos: Chris Sidwells.

Schotte was from West-Flanders, born Alberic Schotte in Kanegem on September 7th 1919, ten months after the end of the First World War. Life was tough for everyone in Flanders back then, the country was devastated during the War, with many of the biggest and bloodiest battles in West Flanders. People there were consumed with re-building, while working to feed themselves in any way they could.

The Schottes were like that, living precariously on casual wages, but they became slightly more secure when they inherited a small farm in nearby Desselgem. Briek was four, they weren’t suddenly rich, the farm depended on family labour and even the kids did their share.

Alberic worked in the fields after school and at weekends, but one day he saw something that changed his life. Desselgem was on the Tour of Flanders route, and ten year-old Briek went to watch the race go by. What he saw was Frans Bonduel hammering past in a blur of colour and speed on his way to winning in 1930. Briek was so excited he couldn’t sleep that night. The drama and speed of the riders, the noise and shouts of the crowd, the coloured bikes and jerseys. By morning his future was mapped out, he was going to be a professional bike racer.

Briek saved every bit of money he could, but it took four long years until he had enough to buy a second-hand racing bike, a Groene Leeuw, Flemish for Green Lion and a big bike brand back then. It was his pride and joy and he couldn’t wait to be 15, so he was old enough to race on it. But one days his father saw the bike, and he threw it into the yard. “These people are the scum of the streets,” he told his son, echoing what many aspirational Belgians thought at the time. It was okay to watch a bike race, something to go and see on feast days and holidays, but professional cycling was a rough business, a business for cut-throats and brigands.

Pro cycling is still a risky career, but it was much worse in the 1930s. A career-ending crash lurked on every corner, there was no health insurance, no team support. Written contracts meant nothing, a few bad races and a career could be over. Very few riders made significant amounts money, and most had jobs during the off-season.

None of that put Briek Schotte off. He was determined to become a pro, not even his father could talk him out of it. He rode his first race two days after his 15th birthday. It was held in the centre of Desselgem on a course marked out by beer barrels. Seven riders started, with Schotte clad in a white shirt and white flannel shorts. He was so nervous he hit one of the barrels, crashed then got up and finished fifth. He won 15 Belgian francs, not an inconsiderable sum in 1934. He gave the money to his mother, he was helping support the family, his chosen career had begun.

Schotte won six races in 1935, then seven in 1936 but he was 17 by then, old enough to work full-time on the family farm, so he had less time to train. Schotte tried to address the squeeze in a number of ways. He got up at 3.30am to train before work, he already gave his prize money to his mother but was determined to get more, and he raced on punctured tubular tyres that he repaired himself to save expense. But the tyres often let him down, and his early morning training and long hours in the fields took its toll.

He was still good, but inconsistent. He won his club championships in Deinze in 1938, and Flemish club championships were hotly contested back then, with professionals taking part if they were club members. Slowly though Schotte became exhausted by working racing and training. He couldn’t carry on, it looked like his dream of being a pro rider was over, but his fighting spirit had brought Briek Schotte admirers, and they saved him.

Many riders in Flanders had supporters clubs based in cafés, some still exist. The café regulars have collections and organise money-raising events to help a bike racer from their village. Many travel to races to offer vocal and more practical support, but in Schotte’s day it was the money they raised that could be a lifeline.

Cyclists came from the working classes, but many of the middle-class and wealthy businessmen enjoyed watching them race. Desselgem is famous for producing linen and several wealthy linen merchants frequented the Café de Welvaert in the town centre, which was the headquarters of Briek-Desselgem, the supporters club formed to help Briek Schotte. When Schotte told the members he was giving up racing the linen merchants had a quick chat together, pooled 1000 Belgian francs and went to see Briek’s father with it.

The money was enough to pay for a farm labourer to do Briek’s job for a year, freeing him up to train and focus all his energy on racing. “They saved my career,” Schotte said years later, and he repaid his supporters by taking his first big win as a professional cyclist right in front of them.

At the end of 1939 Schotte got a place in the big French professional team, Mercier-Hutchinson. It wasn’t a good time to become a cyclist, the Second World War had just started, and as it progressed bike racing was restricted throughout Europe. Flanders, though, was different, the occupying authorities were keen for life to go on as close to normal as possible, and after the invasion bike racing gradually to return to the roads.

The Championships of Flanders is still a big race, and it dates back to 1908. It was always held in Koolskamp, and still is, but the War prevented it being run at all in 1939 and 1940. It was unlikely to go ahead in 1941 too, or at least it was in Koolskamp, but enthusiasts from Desselgem agreed to promote it in their town. Briek Schotte rewarded them with a home win, beating the man who’d inspired him in 1930, Frans Bonduel into second place. Another West Flanders rider Albert Sercu, Patrick Sercu’s father, was third.

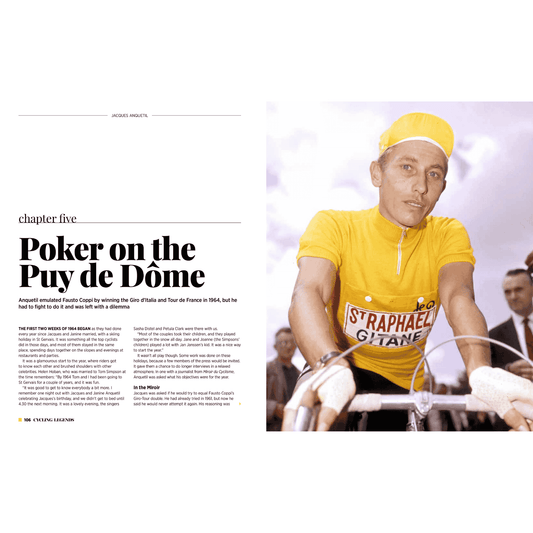

Schotte hit the big time again in 1942 with victory in the Tour of Flanders, when the race finished inside the Sportspaleis in Ghent, but the Tour of Flanders wasn’t a full-on international race that year. Cycling didn’t really get going internationally again until 1947, when the first post-war Tour de France was held. Schotte rode it and won the famous 21st stage, when the lead changed hands on the final day with the Frenchman, Jean Robic winning the first post-War Tour.

The Tour of Flanders got back to full international status in 1948, when Schotte took his second victory. He was 28 years old and reaching his peak. He won races throughout that year, and finished second to the great Italian Gino Bartali in the Tour de France. By September and the world championships in Valkenberg, in the hilly south-east corner of the Netherlands, Schotte was the number one favourite to take the professional title.

There isn’t much space in that part of Holland, so to make the course tough enough to find a worthy champion the organisers chose a ten-kilometre circuit that had to be ridden 26 times for the distance. The 1500-metre long Cauberg, which has an average gradient of 4.6 percent and a maximum of 11, was at the heart of the circuit, with the race finishing at the top.

One hundred thousand spectators crowded around the course, and Schotte’s form was such that he could make the race hard for everybody. After 30 kilometres he was off up the road, three riders going with him, and they quickly built a lead. By half-way the leading four were three minutes ahead of the peloton, but they were about to be joined by three more.

As soon as the three caught the four the escape group lost its cohesion, so Schotte attacked again. Only the diminutive French rider, ‘Apo’ Lazarides could follow him. This is what Schotte told me in 2003 about the rest of that great race; “We eventually got eight minutes’ lead, but then I heard a huge roar from what I guessed was the other side of the circuit. The crowd was thick all the way around, people were shouting all the way too, but this was different. This was like the sound you hear outside a big football stadium when a goal is scored. It was huge and I heard it above the shouts near to me, so I guessed it was the Dutch supporters, who by far outnumbered everyone else. And I guessed it was because their favourite, Gerrit Schulte had attacked.

“I was right and from that point I listened hard. I could hear where Schulte was from the crowd. He was gaining, and he was a good sprinter, so I didn’t want him with me at the finish. I still decided to let him catch us though, but I wanted him to do it just as we started the Cauberg climb. The crowd helped me, I adjusted my speed to how far behind he was while preserving my strength, and I timed it exactly right.

"Schulte caught us as we hit the bottom of the Cauberg with three laps to go, and the moment he did I attacked with every bit of strength I had. I didn’t give him a second to rest. After the effort he made to catch me, my attack finished Schulte. Lazarides caught me, but I wasn’t worried about him. All he could do was hang on, and even if he’d been faking his tiredness it didn’t matter. I knew I could beat Lazarides in a sprint no matter how fresh he was, or how much work I’d done. He was a climber and he couldn’t sprint at all. And that’s what happened, I beat Lazarides in the sprint. That’s how I became world champion for the first time.”

It was a tremendous exhibition of road racing strength speed and nous. Schotte dominated, shaking everybody off his wheel, but still had the tactical sense to do the right thing when Schulte challenged him. It was a virtuoso effort with over 125 miles in the lead. Schotte proved he was unbreakable, and that led to his nickname ‘Iron Briek’. He was a Lion made of iron, and for the next few years he was unstoppable in races that suited him.

Schotte won a second world road race title in 1950, when the championships were held on a circuit based on Moorslede in West Flanders, where Cyriel Van Hauwaert, the first man ever given the Lion of Flanders tag by Flemish bike fans, was born. The Moorslede circuit was flatter than Valkenberg, but Schotte was a master of Flemish cycling, and he won by a minute from the 1947 world champion, the Dutchman Theo Middlekamp.

He carried on winning, especially in Flanders, the last big Briek Schotte victory coming in 1955 when he was 35 years old. It was Ghent- Wevelgem and the first year the notorious Kemmelberg climb featured in the race. Its inclusion handed Schotte an advantage, he knew it well from training.

“The road over the Kemmelberg wasn’t cobblestones all the way in those days. The top section of the hill, over the summit then a bit down the other side, was hard-packed mud. Well, it was hard-packed when it wasn’t raining, but in 1955 it was raining. The Kemmelberg is in West Flanders, so I knew it well from my training rides, and I made sure I was first on the cobbles and still the first when the mud section started,” Schotte told me in 2003.

There was mayhem behind him as riders spun their wheels in the slick mud, came to a stop and toppled over. Most of the field had to walk over the top part of the climb, but while they were doing that Schotte had flown down the other side and was heading for Wevelgem.

He raced until 1959 and his 40th birthday, and for a long time Briek Schotte was the man generations of Flemish riders were compared to. By then he was a team manager, and had almost as much a success as he had been as a rider. Schotte loved Flemish cycling, he was part of its fabric, and he especially loved the Tour of Flanders.

He rode the race 20 times, never missing a year, winning twice and gaining eight other podium positions. Only Johan Museeuw, a man in Schotte’s image, did better than that. But then Schotte did more. As a manager his riders took 11 podium places and five victories in his favourite race, an incredible combined record. His death in 2004 coincided with his favourite race, and his passing was announced during the Belgian television broadcast of the Tour of Flanders. “God must have been one of Briek’s greatest fans,” the commentator said. A great champion from the past had died while other champions raced on the roads he’d made his own.