In the 1950s a bird-like climber fluttered up mountains as if on wings. They called him the ‘Angel of the Mountains’ and he won the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia. His name is Charly Gaul.

Charly Gaul might have climbed mountains like an angel but he was far from angelic. He was a butcher before he was a pro cyclist, and once threatened a rival by telling him he’d get his knives and make sausages out of him. It was not a threat to be dismissed lightly.

Irascible when he raced, Gaul grew grumpier after he retired, and disappeared into the woods of the Luxembourg Ardennes to live as a recluse. Journalists who tracked him down in search of a reason were told; “Go away. I don’t want to talk about my career, it was so long ago. I have nothing to talk about now, so please leave me in peace to be an old grumbler.”

But in 1983 Gaul changed. He met the woman who became his third wife, moved to a suburb of Luxembourg City and began talking again. He spoke about his exile, about how he found it impossible to be with people after he stopped racing. “It’s difficult to go back to normal life after being a cyclist,” he explained. He also said he’d been happy on his own in the woods, growing vegetables. He was happy feeding the deer that came into his garden, it made him feel not just close to nature but part of it.

That was out of his system now. He’d replaced the vacuum cycling left in his life by assuming a totally different one. Now he was ready to live a more normal life. He took a job as an archivist at the Luxembourg Ministry of Sport and it put him back in touch with his cycling story, which he talked about again. And what an amazing story it is.

Charly Gaul was born two weeks before Christmas in 1932 in a part of Luxembourg City called Pfaffentahl. Luxembourg is hilly, which was good for the quite short and very lightly-built Gaul. He won a lot amateur races and quickly became a regular in the Luxembourg national team. He started riding amateur international races, and in 1951 Gaul set a record for climbing the Grossclockner Pass in the Tour of Austria. He was 17.

At 3978 metres (12,461 feet) the Grossclockner is Austria’s highest mountain, and the pass named after it reaches 2502 metres (7772 feet). Years later Gaul spoke about the climb, and about his first contact with high mountain passes: “I’d never seen a road higher than 800 metres before I rode the Grossclockner, but I found I was good on climbs like that. I found a rhythm and it felt natural, and also on that climb the higher we went the colder it got, and that suited me too.”

Gaul set his own pace on mountain passes. He would spin a much lower gears than others did back then, and more often than not shifted into his 27 rear sprocket at the start of a long climb and stayed there. When he was on form, and conditions were right for him, Gaul hated hot weather and rode better when it was cold, his legs would spin to a rhythm that slowly took his rivals beyond their limit. That’s how he broke them one by one, and once the last one was gone, Gaul continued at the same metronomic pace.

“He was a murderous climber, always sustaining the same rhythm, a little machine with a lower gear than the rest of us, turning his legs at a speed that would break your heart; going tick tock, tick tock, tick tock,” was how one of his rivals, the French rider Raphael Geminiani described Gaul’s climbing.

Gaul turned professional in 1953, but it took him a while to find his feet. As an amateur he only rode hilly races. The hills decided the race, all Gaul had to do was pedal. But some professional races are flat, they are all longer, and even stage races with mountains have flat stages too. Gaul didn’t finish his first two Tours de France, but as Luxembourg had few pro riders and the Tour was for national teams in those days, young Charly was always selected.

Eventually, though, he got used to flat stages. He developed a bit more basic grunt, positioned himself better in the peloton, and found the zip to cope with the changes of pace. He even became a good time triallist as he grew stronger.

Gaul won the hilly Tour de Sud-Est in 1955, then survived the first few flat stages of the Tour de France to arrive at the mountains in good shape. He was still a fair bit behind in the overall standings, but that played in his favour.

The first big mountain stage went from Thonon-les-Bains to Briançon, and Gaul attacked from the start. Over the top of the first climb, the Col du Télégraphe, he had a five-minute lead, but because he was 37th overall nobody paid much attention. The contenders certainly weren’t bothered about him, although they were bothered by the top of the next climb.

It was the Col du Galibier, and Gaul had stretched his lead to 14 minutes and 47 seconds. The contenders started chasing, but it didn’t make much difference, Gaul was gone. In Briançon he crossed the line over 13 minutes ahead of the next rider and moved up to third overall.

He lost his third place for a few days, but not by much, then won stage 17 in the Pyrenees. He was third in the next stage and was third overall in Paris. He won the King of the Mountains prize too. In the space of three weeks Charly Gaul had climbed from relative obscurity to one of the best stage racers in the world.

The following year he rode the Giro d’Italia for the first time, and although he won a couple of stage he made little impression on the overall standings until the final day in the mountains. That stage finished on top of Monte Bondone, which is in the Brenta Alps near Trento. Mountain-top stage finishes were a new idea in the 1950s, the first Tour de France mountain top finish was in 1952. They were perfect for Charly Gaul

Gaul was in 24th overall, 16 minutes behind the race leader, but with 242 kilometres and several high passes, he actually thought he could win. Why did he think that? Because it was freezing cold, and rain in the valleys turned to snow whenever the riders climbed.

Despite conditions suiting him, Gaul kept calm, stayed close to the front and waited for Monte Bondone, where he upped the pace and was quickly alone. It’s not a long climb, 12 kilometres, but Gaul took back all his deficit and added enough time on top of it to win the Giro overall, despite stopping half way up to drink hot coffee and change his freezing cycling kit.

He couldn’t walk by the end of the stage, which took him nine hours to complete, but there was carnage behind him. Only 49 of the morning’s 89 starters made it to the finish. What Gaul did was almost super-human, and an annual cyclosportive called La Leggendaria Charly Gaul, starts in Trento and finishes on Monte Bondone to remember his exploit.

Gaul’s remarkable Giro victory maybe made him too confident going into the 1956 Tour de France, because despite winning two stages and the King of the Mountains, he had some bad days and ended the race in 13th place overall.

Gaul was fourth in the 1957 Giro d’Italia and third the following year. He was 25 years old and entering his best years, but prone to bouts of self-doubt and to bad days on the bike. His good days outweighed his bad ones in the 1958 Tour de France, though, he was amazing in that race.

He won four stages, including the first-ever time trial up Mont Ventoux in a time of 1 hour 2 minutes and 9 seconds, a record that stood for 31 years. He’d had a very bad day earlier in the race and lost a lot of time, so despite winning on the Ventoux he started the last day in the mountains eight minutes down on the race leader, Raphaël Geminiani. It didn’t matter, Gaul had been waiting all the race for a day like this.

The stage went from Briançon to Aix-les-Bains with a finale running through the Chartreuse Massif. There were five mountain passes to climb and it was raining, really raining. Gaul’s team manager knew it was a perfect day for his rider, and woke him with the words; “Come on soldier, this is your day.” Gaul looked outside, and his confidence soared.

Gaul believed he’d the lost the previous year’s Giro d’Italia through a gross breach of rider etiquette. He stopped to take what cycling commentators like to call a ‘natural break’, and several riders attacked, including the French three-time Tour de France winner, Louison Bobet. Gaul had a long and futile chase, at the end of which he swore revenge on Bobet. Today in the rainy Alps he was determined to have it.

Gaul was so confident he went looking for Bobet before the start, and when he found him he started winding him up. He told the Frenchman that if he really wanted to win this Tour de France, he needed to follow Gaul on this stage. “And to make it easy for you,” he said. “I will tell you what climb I will attack on today, it will be the Col de Luitel. It’s the second climb on the stage, just so you know. I can even tell you on which bend I will attack.”

Bobet wouldn’t rise to it, he just blanked Gaul and walked away. The stage started and a small group of riders moved clear. At the top of the first climb, the Col du Lautaret, the group was led over by another formidable climber, Federico Bahamontes. They had a couple of minutes over the peloton, but between the peloton and the leading group Gaul was chasing.

Nobody reacted when he attacked, the top riders thought Gaul was too far behind overall to bother with. They even thought he’d gone too early to win the stage, so they weren’t worried. They should have been. When they heard Gaul shouting the odds at Bobet at the stage start they could see what sort of mood he was in.

Gaul joined the front group on the descent of the Lautaret, and kept riding as hard. Soon he only had Bahamontes for company. They came to the Col du Luitel, and Gaul accelerated. He dropped Bahamontes and romped clear, and as he did the rain switched from heavy to torrential.

Conditions turned from bad to terrible, some riders said they could hardly see through what they described as a curtain of water. The whole field was cold, suffering and losing to Gaul. He was oblivious to the weather and to the rest of the Tour riders, he just kept beating out that infuriating rhythm of his and didn’t let up until the finish.

He won the stage by nearly eight minutes. The last rider was and an hour and seven minutes behind him. Gaul moved up to third place overall, a smidge over one minute behind the new race leader, Vito Favero of Italy. Two days later Gaul won the 74-kilometre final time trial to take the yellow jersey, and next day he won the Tour de France.

The previous year’s winner, the new star of France, Jacques Anquetil didn’t start the final time trial because he was suffering from bronchitis. The French national team was annihilated. Third placed Frenchman, Raphael Geminiani, rode for the Centre-Midi regional team. The best placed rider form the French national team was Louison Bobet in seventh overall. The team was booed at the Parc des Princes stadium, where the Tour de France finished in those days.

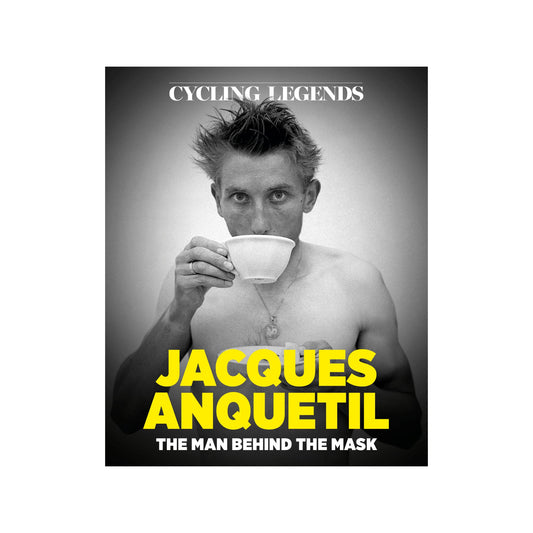

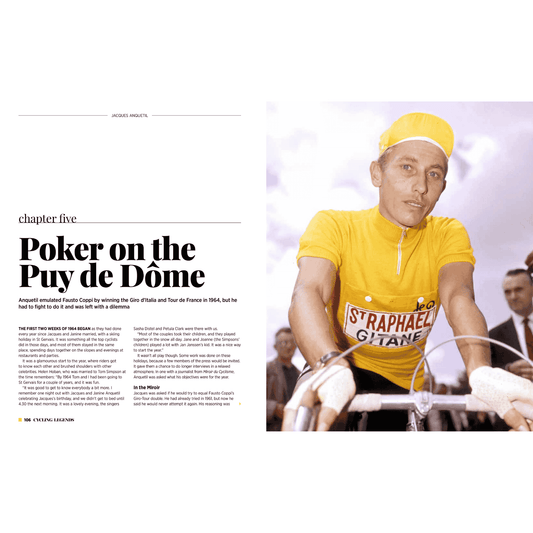

Jacques Anquetil hated the experience of 1958. He joined his French team mates in Paris, and the booing and whistles hurt the ice-cool looking Frenchman so much that in better times, after he won his next Tour de France in 1961, he bought a speedboat and called it Siffles de 1958 (Whistles of 1958) so it reminded him of what it’s like to lose. The experience of 1958 also left Anquetil with a recurring nightmare.

In it Gaul would be with Anquetil then accelerate away from him. Anquetil would slowly close the gap, but once level with Gaul he saw his rival was made from millions of raindrops. This image of Gaul would then melt before his eyes, only to re-form up the road riding ahead again. Anquetil had to chase all over again until he caught him, at which point raindrop Charly would disappear. And so it went on until Anquetil woke up in a panic.

Gaul was a living nightmare for Anquetil too. He was beaten again by the Luxembourger in the 1959 Giro d’Italia. Anquetil led the race by four minutes at the start of the penultimate stage, which went from Aosta to Courmayeur. It looked a sure thing, but the stage climbed the Col du Petit St Bernard.

The Petit St Bernard really suited Gaul. Its average gradient is only five percent but it is 30 kilometres long, gains 1400 metres in height and climbs to 2200 metres. Gaul could click into his rhythm and go for it, and that’s just what he did. He rode at close to 30 kilometres per hour all the way up the Petit St Bernard.

One by one the opposition melted away. Anquetil, who could suffer like no other, held on until three kilometres from the summit. He was the last to stay with Gaul, but even he cracked, and cracked so badly that he lost seven minutes by the top and ten by finish in Courmayeur. Charly Gaul had won another Grand Tour with one incredible day on one incredible mountain effort.

Gaul was a delight to watch in a race, but was less delightful to know. He was often prickly with his fellow racers, and developed a reputation for meanness. He rarely shared what he won with team mates, and sharing is a tradition in the pro peloton. He made more enemies than friends.

His career continued into the 1960s with high spots of third in the 1960 Giro d’Italia and fourth in 1961. He also finished third in the 1961 Tour de France. But he became increasingly paranoid, thinking that other top riders were combining against him. It wasn’t far from the truth on some occasions. Gaul also went through troubles at home and split with his wife.

He started the 1962 Tour de France, but was a shadow of his former self and finished ninth without any stage wins. He was hesitant and indecisive in the peloton, saying that there were too many crashes in cycling now. “I’m scared in the peloton,” he confessed. He wasn’t winning, and he lost his earning power because of it.

Gaul was good at cyclo-cross and repeated his 1954 victory in the 1962 Luxembourg national cyclo-cross championships. A few weeks later he equalled his best-ever finish in the world cyclo-cross championships with fifth place. Gaul usually did some cyclo-cross events during the winter, and won several of Luxembourg’s biggest races, but now he used ‘cross to make money. He won his sixth national road race title in 1962 as well, but it was his last title, and his last big victory.

He carried on through 1963 with the Peugeot-BP team, but did nothing. He rode for a tiny Belgian team, Lamote after that, but was so bad in races that some fickle fans booed him, while the more loyal appealed for him to stop racing, which he finally did in 1965.

Gaul opened a bar near the central station in Luxembourg City, but hated having to make small talk with his customers and listen to their endless opinions. He also hated re-hashing his glories for them. He couldn’t live like that, he’d been the Angel of the Mountains and yearned for the freedom that gave him. Now he was earth bound, wings clipped, he did the only thing he could do and ran away to the woods to start a new life.

Those who met him during his exile said he looked and sounded sad, but later on he said he hadn’t been. Once back in society he renewed his acquaintance with cycling. The 1989 Tour de France started in Luxembourg, and Charly Gaul was its guest of honour. He appeared in a 2002 group photo of all the surviving Tour de France winners, and he followed the career of another great climber, Marco Pantani; a complicated and far more troubled figure even than Gaul. Charly Gaul died in December 2005, two days short of his 73rd birthday.

1 comment

reading > Angel of the Mountains< by Paul Maunder

an excellent read about Charley Gaul not not only describing the extreme athlectic efforts to compete

in this one thoughest sporting events but also the mind games and mental strengths

required to compete in this endurance sport.