“So I went to see him, I sat down in front him and he said; “Right, I’ll give you this much to ride for me,” and he wrote down a figure on a piece of paper and held it up. I looked at the paper and didn’t know what to say, so he said. “Ok, you hesitate, I’ll try again,” and he wrote down another number.

“The first figure was far above anything I would ever have asked for, so I was stunned when he held the second figure up. Then Borghi said, “I see you still hesitate. Well, I can do even better than that, and what’s more if you sign a contract with me now I will pay you up front three years’ salary in advance, and I will pay it today.’”

Baldini signed, he would have been a fool not to. And when he did, true to his word Borghi wrote out a cheque for an amount of money that roughly equaled £40,000, and pushed it across his desk to Baldini. In 1958 £40,000 was an enormous amount of money.

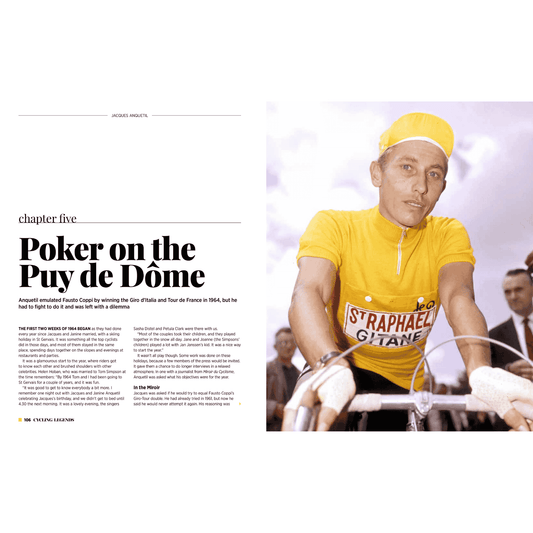

But Borghi’s act was a measure of Baldini’s place in cycling at the end of 1958. He was a second year pro who won almost everything he rode, and won everything with seeming ease. His potential was immense. No classic or Grand Tour looked beyond Baldini. The Coppi era was over, Louison Bobet’s was drawing to a close, Anquetil wasn’t yet the dominant figure he would be. This was Baldini's time, but from the moment he signed his contract with Borghi, the brilliant Baldini with all that potential slowly disappeared.

Great expectations

In 1959 he won some time trials, he was sixth overall in his first Tour de France, which was good result, Baldini was still only 26, but the fans and press expected more; a lot more. The following year, Baldini only won one race.

Cartoons appeared depicting Baldini struggling up a mountain, weighed down by a bag of gold. The fans jeered, shouting in his ear that didn’t ride hard anymore because he was too well paid.

He told René De Latour; “People think it’s the money that stops me training properly, but I train as hard as I ever have, and I haven‘t altered my methods.” But De Latour countered by saying that Baldini let his weight rise too high during the winter. Baldini agreed, but said that he worked like mad to lose it.

Baldini did put on weight quickly, but often it was while he was laid low with some injury, and that didn’t help. “I had to have many lay-offs, including one that necessitated a tricky operation on my leg, and in that time I put on weight. I had to fight twice as hard to get rid of it, so I was constantly going into races tired. It just became a vicious circle,” Baldini explained many years later.

At the end of his three year contract with Borghi, Baldini was embarrassed by his lack of results, and at the amount of criticism that had been heaped upon Borghi. “He did nothing wrong, but the press said that his money had spoiled me,” Baldini said.

Cycling was a very different world in the 1950s. Sponsors like Borghi, rich men with successful business from outside of cycling, were a new feature of the sport, and some elements of the press and fans resented them. Borghi was accused of being interested in cycling only for the publicity, whereas that would be taken as read today.

To show that this wasn’t true, and that he was in cycling because he loved it, Borghi launched a team in 1962 that was called the Musketeers. Its riders had no advertising on their clothing at all, and Baldini volunteered to ride for them for free. It was a noble act, but it brought no more results than the previous year had. Baldini was still locked in a cycle of injury, lay off, rising weight, then training too hard to lose it and ending up with another injury or illness.

Flashes of brilliance

In between the down times he had moments of brilliance in time trials, including a three minute thrashing of Jacques Anquetil in Baldini’s home race the GP Forli in 1962. Anquetil was at his peak then, and Baldini proved he could still be better, but it didn’t last. He couldn’t string more than a few weeks of good form together any more.

Borghi pulled out of cycling at the end of the season and Baldini raced for the Swiss team, Cynar-Frejus in 1963, winning six races. He signed for Salvarani in 1964 but the magic had gone. He ended his racing career on November 4th that year by riding to second place in the Baracchi Trophy with Vittorio Adorni. At 31 Baldini was tired of struggling, and anyway he’d invested the money he earned in rich farmland around his home so he didn’t need to struggle to win bike races any more. There was no point, there was nothing left for him in the sport.

Did Borghi’s money ruin Baldini? Or was it his injuries and the subsequent fights to lose weight? Perhaps they were both factors, but better we judge him for what he achieved between 1956 and 1958. World Records, world and Olympic titles, as well as winning a Grand Tour. For three years, summer and winter, Baldini was the brightest star in cycling, but maybe he burned too quickly. He was the Supernova of Cycling.

1 comment

An amazing story Chris.You certainly researched it well.It’s so sad that he did not continue to win into his thirties but everyone looks for reasons and perhaps there are none.Keep up the fantastic series.