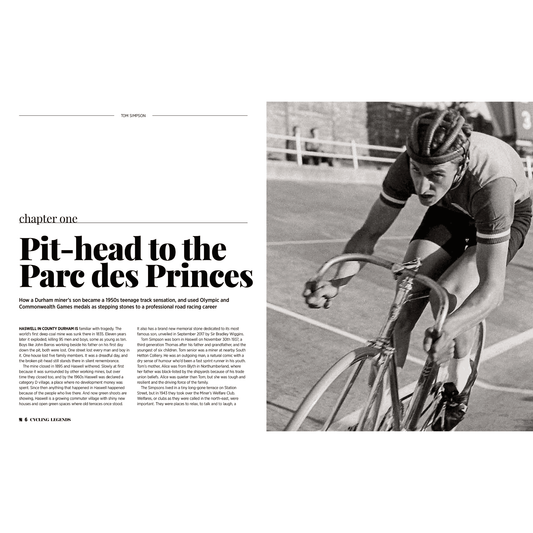

A rainy day in Spain 60 years ago, a hilly circuit in San Sebastian, hours of struggle reduced to two men and one kilometre of rain-soaked road to find a world champion.

It was a straightforward duel for a rainbow jersey between two gentlemen, a German and an Englishman. Rudi Altig and Tom Simpson looked nothing like champions two months ago. Altig was on crutches recovering from a crash, and blood poisoning had stopped Simpson in the 1965 Tour de France, but here they are, the best of the best contesting the men’s pro road race world title.

Tom damaged his left hand descending the Col d’Aubisque in the 1965 Tour, and his wounds weren’t fully cleaned by the attending medic. Infection set in overnight, then blood poisoning. Simpson should have stopped, but he tried to carry on. He did one more stage, then the Tour de France doctor refused to let him go further.

Tom was taken to hospital, where at first doctors thought he might lose his hand - it was that bad, that serious. He was operated on, drains were inserted into the infected hand and powerful antibiotics used to fight the poisoning that gripped his whole body. He was moved to a hospital in Ghent, where he lived, and started responding to treatment. A few days later he was released and cleared to start training.

Tom Simpson leaving the 1965 Tour de France in an ambulance

Road to Spain

This disastrous Tour meant Tom didn’t have many post-Tour criterium contracts to fulfil, but that gave him time to follow a structured training plan, and he quickly regained fitness. He began looking forward to the 1965 road race world championships, and as he always did, began to hope.

The British team for the race was small but very able. Tom was joined by Barry Hoban, Vin Denson, Michael Wright, Alan Ramsbottom and Keith Butler. They all raced for top ranked European pro teams at the time, and were respected riders.

They would go up against ten-man teams from the mainland European nations, but the British riders had a plan, they believed in Tom. They would do everything they could to help him.

Out of the public eye

Tom had been out of the public eye, but was training hard by racing in Belgian kermesse races and riding to and from them. It was the classic way Belgians prepared for the worlds back then, and had proven successful many times.

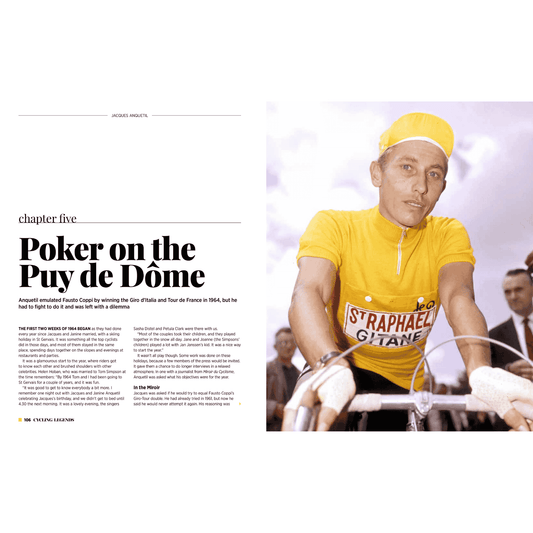

With no recent form the press didn’t rate Simpson as a favourite. That was Jacques Anquetil. He hadn’t ridden the 1965 Tour, training for the worlds instead. But Anquetil’s closest team mate, Jean Stablinski wasn’t convinced of his leader’s chance, because he’d seen how well Tom was going.

Stablinski lived in northern France close to the Belgian border, and he’d done some of the kermesses Tom rode. Looking back on that time Stablinski told Chris; “I saw Tom arrive quietly on his bike, then leave on it after the kermesse, and I felt his power during the races too.

“He would attack or push hard for no reason, then drop back, then go again. He’d back off towards the end, not wanting a result to attract attention. He didn’t want to go into the worlds as a marked man. It was a very clever approach.”

Jean Stablinski witnessed Tom's strength in pre-worlds kermesse races.

Rain in Spain

The 1965 pro worlds was 14 laps of a hilly 19-kilometre circuit based on a small town near San Sebastian called Lasarte. “We got there a couple of days before the race, and Tom had all of us out at eight o’clock the next morning. It was pouring with rain, but he wanted to ride the circuit so he could get to know it. We did a few laps then went off for a loop in the hills, and you could see Tom was flying, he was pedalling beautifully,” Vin Denson remembers.

Barry Hoban also shared his recollections. “We stayed at the same hotel the rest of the British team stayed in, but we paid our own way, the pro’s had to. Tom supplied us with Great Britain jerseys he’d had made in Italy, and paid for himself. The British team used Raxar jerseys, which were awful to wear. I don’t know what they were made of but it rubbed your skin. The jerseys Tom had made were soft wool, a good fit and they kept their shape.”

Ninety-six riders started the pro road race, and Hoban outlined the British plan. “Tom asked me to go with any breakaways, but not work with them. Then if a move looked promising he’d try to get up to it, and once he got there that’s when I should start to work.

“I’d ridden the Vuelta a Espana the previous year, winning two stages, and every day Spanish and Portuguese riders attacked from the start. More often than not you scraped them up before the finish, but they still kept attacking, and they attacked in San Sebastian. I knew they would.”

Barry Hoban (nearest camera) played a crucial role.

Promising

Hoban covered the attacks, got in a solid breakaway, but thought it was doomed. Then Roger Swerts of Belgium and Peter Post joined it, then the Italians Franco Balmamion and Bruno Mealli, then Karl-Heinz Kunde of Germany and a few others.

This was different, this was promising. Post, Balmamion and Swerts were all capable of winning, and they had strong teams behind who wouldn’t chase if they were up front.

This information filtered back to Simpson, who approached two of his team mates. Vin Denson again: “Tom asked me and Alan Ramsbottom to take him to the front then attack. He wanted us each to do a turn, then he’d go. It was like in a lead out for a sprint, and we did it exactly as Tom said.”

Denson and Ramsbottom launched Simpson clear of the main bunch. Rudi Altig saw what was happening and sprinted after him, and the two started working together. They quickly caught the front group, and that was Hoban’s signal, “Now I started working. Tom was working, Post, Altig and the Spanish riders were all working, plus some others,” he says.

The group started pulling away. Ward Sels of Belgium and Jean Stablinski tried to get across, but their move failed. Then when they were caught, with all the big cycling nations apart from France represented in the breakaway, the bunch slowed down.

Solo lap

Jacques Anquetil knew the title was slipping away, so tried to get a chase going, but with just his team working they didn’t make any impression on the break. In the end Anquetil did a whole lap solo on the front of the bunch, but made no impact on the lead. The race was over for everybody but the breakaway.

The effort by Anquetil was never forgotten by Keith Butler. This is what he told Chris when they met in 2014. “Tom asked me to watch Anquetil. If I just did that and nothing else he’d be happy. It was a big ask but I was determined not to let Tom down, so I followed Anquetil everywhere. Including when he did that lap!

“It was so impressive, the constant speed he set was incredible. I suffered like I never had before to hang on, but I did it. I was so shattered at the end of the lap, though, I had to pack in the race.”

Passengers

Up front the size of the group, and the increasing number of passengers in it, worried Tom. Barry again: “Swerts hadn’t done much, and Balmamion stopped working. Tom was concerned about that, in fact he joked about it. He asked me how I was feeling, so I said I was a bit knackered, which I was by that stage. He said that if I felt like falling off could I fall off in front of Balmamion. I knew what Tom was going to do, I knew he was getting ready to attack.”

Simpson made his move on a climb. It wasn’t a steep one, but it was quite long and it was followed by a stretch of false flat. The perfect place for a strong rider to go.

“I was riding so well that day I didn’t think I could be beaten in a straight fight, but I was concerned about the riders who weren’t working in the break, so I needed to do something. I just hammered all the way up this climb in my big chainring and didn’t look behind me. Rudi Altig was able to follow my attack, but that didn’t change anything. I still knew I would win,” Tom said afterwards.

Simpson makes his big move, only Rudi Altig can follow.

At the top of the hill he moved across to let Altig do his turn at the front, and as he did Tom shouted, “Come on Rudi, remember the Baracchi last year.” That must have given the German rider confidence, because he’d been the stronger of the two in the 1964 Baracchi Trophy two-man team time trial. They worked well together, agreeing to play to each other’s strengths by Altig doing the lion’s share on the flat, and Tom leading up all the hills.

They worked like that until they were 1000 metres from the line, where they separated: “We agreed to work together until one kilometre to go, then we would decide the race,” Altig said afterwards.

Altig and Simpson with one lap to go.

Tactics

Tom had his tactics worked out. Thinking Altig wouldn’t expect him to go early he shifted to a lower gear. As Altig moved over to take his side of the road, Tom attacked as hard as he could.

He got a gap, shifted to a higher gear, put his head down and went for it. Altig was taken by surprise, he hesitated, then it took a while to get on top of the gear he was in, then his legs buckled. “I fractured my hip earlier in the year and I was short of training and competition,” he told reporters.

Tom described the last moments of the race like this; “When I looked down I could see Altig’s reflection in the wet road surface, and I kept thinking he’s coming, he’s coming. Then suddenly the finish line flashed beneath me and I thought - he hasn’t come past, I’ve won; I’m the world champion.”

Tom wins the title

At home

Tom’s wife Helen, now Helen Hoban, was watching the race on TV at their home in the St Amandsberg suburb of Ghent. Some friends were with her, but after Tom got into the break, and particularly when he got away with Altig, the house started filling with other people.

“I couldn’t believe it, there were people I didn’t even know. I was rushing outside to tell my neighbours what was happening, then back to the TV through this crowd of people. I don’t know how many turned up and were watching with us, but the house was packed.

“And when Tom won; well, there was one guy, a young English rider, I can’t even remember his name, he jumped up, fell back down and broke the sofa. Everybody was so happy. It was unbelievable. And then flowers started arriving. I quickly ran out of vases to put them in,” she remembers.

Mobbed

Tom was mobbed at the finish. The man who ran his supporters club in Ghent, Albert Beurick, who was working as unpaid support for the British team at the worlds, picked Tom up, bike and all, and held him aloft. “I didn’t know my own strength at that moment, I was so full of joy,” he said many years later.

Within minutes of having the rainbow jersey on his shoulders Tom was signing contracts to ride critériums and track meetings all over Europe. He had time to get changed, a quick glass of champagne with the British team, then headed for a flight to Paris for a critérium there next day.

In the rush Tom left his bag with his rainbow jersey and medal in it with the rest of the British team’s luggage. They were later reunited, but the outgoing world champion Jan Janssen remembers: “I had to lend Tommy a rainbow jersey in Paris. I was so pleased to see him as world champion. He was a very special person, a talented rider who always smiled, who was always joking. I had some of my best times in cycling with Tommy, I called him Tommy because it’s the Dutch way, and I often think about him, even now so many years after he died.”

Riding the six-days as world champ with Peter Post (left)

Celebrations

Without their new world champion the rest of the British team celebrated quietly, content with a job well done. Vin Denson remembers a lovely conversation he overheard in the team’s hotel later that evening.

“Two old English ladies were staying at the same hotel as us, quite posh they were. They were doing a tour of European cities and resorts. Anyway, the organisers put on a fireworks display in San Sebastian to celebrate the end of the world championships, and I’ll never forget overhearing those two old dears.

“One of them asked the other, “What is everybody celebrating?” And her friend replied, “It seems that a young man from Doncaster has won the annual fireworks competition dear.” Tom would have loved that.”

Next day the British team split up and made their way home, with Hoban driving Simpson’s car. “Tom loved his cars and he’d just bought a BMW 1800 TI/SA, the TI stood for Turismo Internationale, they were performance cars used in touring car races.

“So I had this lovely fast car to drive through the top of Spain and up through France into Paris, where Tom met me outside the Gare du Nord. I handed him the keys and he jumped in and he tore off up the road. He had to get to a reception in Ghent, while I caught the train back to northern France, where I lived at the time.”

Helen Hoban takes over; “Almost as soon as Tom got home a crowd of people turned up in front of our house. There were so many people Tom had to go to an upstairs window so they could all see him.

“He was in demand everywhere. He got the freedom of Sint Amandsberg. His mum and dad came over for that, and we were driven through town in an open carriage.

“By then Tom had won the Tour of Lombardy as well. I went to Italy and saw him finish at the track in Como, it was wonderful. But no sooner was that done than he was riding six-day races all over the place.”

60 years on

What Tom Simpson did on that rainy day in Spain was truly ground-breaking. He was the first British cyclist ever to win the title, and the only one since him to win it, now called the men’s elite title, is Mark Cavendish.

When you add Simpson’s 1965 Il Lombardia victory in the rainbow jersey, and his becoming the first cyclist ever to win the BBC Sports Personality of the Year award for 1965, this year is an important anniversary of something that would still be quite astonishing today, even with recent British cycling success.

Cycling Legends Media is determined to remember and celebrate it throughout this year with several Simpson inspired events, culminating in our Tom Simpson Cycling Festival in Harworth, the North Nottinghamshire town Tom grew up in, running from 7 - 14th September 2025.

Find out more here - https://cyclinglegends.co.uk/pages/tom-simpson-cycling-festival

6 comments

A great article about my hero in cycling and I remember getting his autograph at the cycling show at Earls Court where he was riding the rollers I was just a school boy and hoped that one day I could be like Tom.

A classic account Chris. Many thanks.

A great article Chris.

I really enjoyed this piece, which popped up in my Facebook feed. Great insight and detail, with some excellent photographs. I have now subscribed to the newsletter and will look forward to it!

What a great article Chris well done