Jacques Anquetil could turn a hopeless situation into a miraculous win. His unprecedented runs of victories in big races was proof of that. None of his exploits, however, compared to what he achieved in 1965.

The cast of this story, (left to right) Jean Stablinski, Raphael Geminiani, Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor.

Bordeaux-Paris was a classic one-day race in the 1960s. It wouldn’t be allowed today. Cycling’s governing body would never sanction a 580km single-day WorldTour event.

That’s how long Bordeaux-Paris was. Riders started in darkness at one o’clock in the morning in Bordeaux, in the south-west corner of France, and hoped to arrive in Paris late in the afternoon that same day.

Picture in your mind what it would take to win a race like that.

Now imagine trying to win Bordeaux-Paris the day after winning a mountainous, week-long WorldTour stage race, with barely two hours sleep between both.

Impossible? That was the madcap challenge Jacques Anquetil attempted in 1965. Read on to find out why, and how he did it.

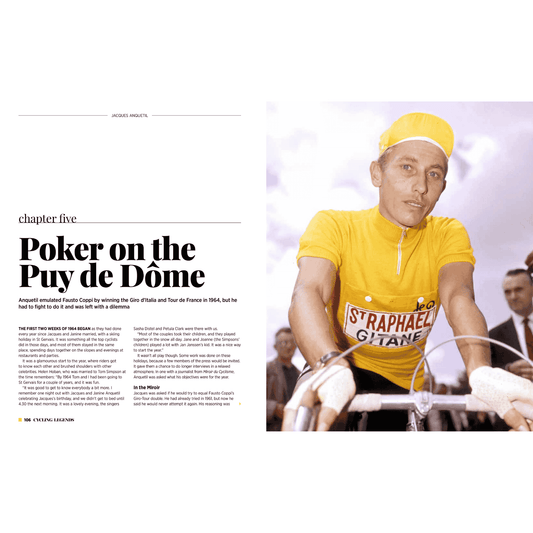

Anquetil in the Maglia Rosa of the 1964 Giro d’Italia

Anquetil in the Maglia Rosa of the 1964 Giro d’Italia

From 1962 until 1964 Anquetil raced for a French team sponsored by the drinks company St Raphael. His three Tour de France wins and a Giro-Tour double in that time gave St Raphael serious bang for their sponsorship buck.

However, when brands achieve widespread recognition in one demographic – in this case followers of cycling – new markets beckon. St Raphael ended its cycling sponsorship at the end of 1964, and Anquetil’s team needed to find another backer.

Anquetil’s team was the biggest outfit in cycling, and brands were lining up to be associated with the French champion. One of few with pockets deep enough to afford Jacques and his team was the French arm of the Ford Motor Company, Ford France.

Tour bust-up

The transition was seamless, but behind the scenes team manager Raphael Geminiani had a problem. Ford France – because it’s THE biggest race and he’d won it five times – not surprisingly wanted Anquetil to ride the 1965 Tour de France.

But Anquetil refused.

Geminiani had known this when he signed up Ford France. Of course, he didn’t tell them, the team badly needed a big sponsor. Ford France had the resources, and he thought he could change Anquetil’s mind. He had succeeded in the past, but this time Anquetil refused to budge.

The 1964 Tour was exceptionally tough

The 1964 Tour was exceptionally tough

Jacques was physically and mentally exhausted by the end of 1964.

He’d won the Giro d’Italia that year, but had to fight for it. Raymond Poulidor had pushed him very hard, almost to breaking point, in the Tour de France.

Anquetil once again came out on top – becoming the first rider in history to win five Tours de France.

And in winning the 1964 Tour he became the only rider at that time ever to repeat Fausto Coppi’s Giro-Tour doubles of 1949 and 1952.

Poulidor (right) pushed Anquetil very hard in the 1964 Tour de France

Poulidor (right) pushed Anquetil very hard in the 1964 Tour de France

At that point in the history of cycling Jacques Anquetil was up there with Fausto Coppi, arguably the two greatest cyclists of all time, to date.

He was far better than Raymond Poulidor – most pros of that era agreed – but in private, Anquetil’s fragile psyche had allowed Poulidor to get under his skin.

Anquetil was plagued by the thought that if events turned against him in the 1965 Tour, Poulidor might beat him. The thought of defeat at the hands of Raymond Poulidor, at that time, in any race, Anquetil found intolerable.

The reason? For all his seeming mastery on the bike, Anquetil had developed a totally irrational jealousy of Raymond Poulidor.

Poulidor was considerably more popular in France, especially rural France, than Anquetil. The author and journalist Jean Bobet explained why: “French people like the underdog, they feel genuine affection towards them. Maybe they identify with them a bit, feel like they need their sympathy and their support. Likewise they feel champions don’t need that.”

Anquetil felt this keenly. He knew he’d been riding his luck. He wasn’t going to risk his reputation in the 1965 Tour de France. Why should he? He’d won a record five Tours.

He was the greatest Tour de France rider ever, why throw it all away for one more victory when he’d already won two Tours more than anyone else in history.

Geminiani had a big problem.

Ford France was bankrolling Anquetil, his team and back-up staff, and was expecting a return on its investment. The Tour de France had global reach, nothing else came close.

Geminiani would have to come up with something bigger, and he did.

Anquetil winning the Criterium du Dauphine in 1965.

Anquetil winning the Criterium du Dauphine in 1965.

What if Anquetil did something considered nigh-on impossible? It would be unprecedented, a challenge that people would think he was mad for even attempting.

It would be something that would generate loads of publicity, maybe even more than a sixth Tour de France win, and certainly more positive news than a Tour de France defeat at the hand of Raymond Poulidor.

What if Anquetil rode and won the Critérium du Dauphiné, then travelled straight to Bordeaux for the start of Bordeaux-Paris, and won that too?

Nobody had ever thought of doing that, let alone attempting it. It would certainly make headlines – the week-long and mountainous Dauphiné stage race finished on a Saturday afternoon, and Bordeaux-Paris started VERY early the next morning.

It would be a physical and logistical nightmare, but if Anquetil won them both Raymond Poulidor could win the Tour de France and it wouldn’t affect him one bit.

People would still be talking about Jacques Anquetil long after Poulidor won the Tour, and Ford France would have a unique publicity coup.

“He didn’t like it though,” Geminiani told me when I asked about the exploit. “He refused to consider it for a long time because he was afraid of failure.

“However, I was convinced he could do it. Why? Because the Dauphiné was a race he’d already won, and riding behind a Derny pacing bike, as the riders did for the last 160 miles of Bordeaux-Paris, Anquetil could go very fast.”

I asked Geminiani if proximity of the two races, and that Anquetil would get almost no rest between them, had worried him. “Of course it did,” he replied, “but Anquetil had powers of recuperation that I’d never seen before. He appeared thin, but he was very powerful.

“Still, he kept saying, ‘it’s impossible, I can’t do it because it’s too hard’, but I told him I believed in him. I told him that if he succeeded then that was great, and if he failed I would assume full responsibility.

“That seemed to satisfy him a bit. What clinched it though was when I told him that if he achieved this double, Poulidor could win the 1965 Tour de France and nobody would notice. They would still be talking about Jacques Anquetil.

“He thought for a while, smiled, then said he’d do it.”

The incredible double

Geminiani’s plan started to pay off when news of the exploit was announced. The press went wild, though what they said wasn’t all positive. A number of journalists pointed out that the Dauphiné was a mountainous race and Anquetil would be up against a very much in-form Poulidor.

What’s more the race didn’t finish in Avignon until late afternoon on Saturday 29 May, and Avignon was deep in the south-east of France, while Bordeaux was on the other side of the country. And Bordeaux-Paris started at one o’clock the next morning, just one hour into Sunday 30 May.

Getting from one side of France to the other would rule out any meaningful recovery time. And Bordeaux-Paris involved riding 584 kilometres (365 miles) non-stop.

Surely impossible – some pundits said it was positively dangerous.

“I agreed with some of what the journalists said,” Geminiani told me. “The main problem was logistical, and I didn’t know quite how to deal with it.

“Ford France helped by putting a powerful Ford Taunus motor car at our disposal, with a racing driver at the wheel, but it would still be a tiring and probably nerve-wracking journey racing across France by road in the dead of night.

“Then out of the blue I got a phone call. A voice at the end of the line said, ‘Monsieur Geminiani, there will be a military plane waiting for you and Jacques at Nimes airport, courtesy of Charles de Gaulle’.

Inside President De Gaulle’s private jet

Inside President De Gaulle’s private jet

“President De Gaulle was a big admirer of Anquetil, so we used the plane. It only had a few seats; one for Jacques, one for me, one for a mechanic and one for a journalist who took photos for all the press.

“We used the Ford Taunus to get from Avignon to Nimes, and another Ford car met us at Bordeaux airport. That took us to the hotel where two Ford France riders, who Jacques had asked to help him in the race, were already staying.”

Anquetil’s team-mates were his most trusted lieutenant, a Frenchman of Polish extraction called Jean Stablinski, and a very strong British rider, Vin Denson.

Denson remembers Anquetil’s arrival: “We’d just sat down to eat. It was breakfast, I suppose, but it was 10.30 in the evening.

“I’d ordered steak and pasta, which was the pre-race staple food for bike riders in those days, and was about to eat it when Jacques rushed in the room, saw me and said ‘I’m starving, let me eat that one and you order another, because I need to eat quickly then grab some sleep’.”

Denson looks back fondly on his time at Jacques Anquetil’s team: “It was like being with Manchester United. If you were with Jacques you got to meet all sorts of famous people – politicians, film stars, writers, artists and musicians.

“I remember before one race in the South of France we were invited to a reception at the royal palace in Monaco. Only Jacques and the Ford France team were there, and we met Prince Rainier and Princess Grace, so that was royalty and a film star in one day, because Princess Grace was Grace Kelly before she married,” Denson said.

In Bordeaux, Anquetil was very tired when he arrived at the hotel, and after eating Denson’s “breakfast” he went straight to bed, reckoning afterwards that he got about two hours sleep before Geminiani woke him to get ready for the one o’clock race start.

A tough Dauphine

The Critérium du Dauphiné is always a hard race, but bad weather and Raymond Poulidor made the 1965 edition extra hard.

Rain turned to sleet in the valleys during the two toughest mountain stages, then snow higher up, and Poulidor was absolutely flying.

Anquetil still managed to win, taking three stages along the way, though he gained more time over Poulidor by winning bonus seconds in intermediate sprints.

Poulidor tried to rely on his climbing to make a difference, but while he managed to distance Anquetil at times, the five-time Tour winner always found enough to close the gap or peg back his lead.

Anquetil eventually won by one minute and 43 seconds from Poulidor, while third placed Karl-Heinz Kunde of Germany was well over six minutes behind.

The first leg of the ‘impossible’ double was completed, and although there was a long way, literally, to go and many things had to fall into place, Geminiani was increasingly confident.

“Okay, Jacques was tired, I knew that, but I also knew he was in great form, and I knew Bordeaux-Paris suited his strengths. It would be hard, especially during the night-time, because at two or three o’clock in the morning your body is telling you to sleep, not ride a bike. But if we could get him through that I was confident Jacques would win,” he told me.

Black night of the soul

It was a dark night for Anquetil, though. He complained about the cold, about how empty and stiff his legs felt, and he told his manager several times that he was tired and just wanted to sleep.

Geminiani nodded, said he understood, then ignored him.

Geminiani also told Vin Denson and Jean Stablinski to ride either side of Anquetil, to not leave their position and above all, not let him stop apart from for calls of nature. Even then, he told them to hustle Anquetil back to his bike as quickly as possible.

Denson remembers that night: “Jacques was riding so close to me his shoulder would occasionally brush mine. I tried chatting to him but he wasn’t interested, he was just suffering.

“To help him I pushed him for long stretches, so he could save energy. Then there was one time I was pushing him and he started leaning on me. He wasn’t pedalling, and I’m sure he fell asleep for a few seconds, maybe a minute.”

It was a long bleak night. In Paris later that day Anquetil told reporters that the worst part of the whole Dauphiné and Bordeaux-Paris exploit was the night he’d just experienced.

“They say you have to have a bad patch in Bordeaux-Paris, well, mine lasted 300 kilometres,” he told them. What he didn’t reveal was a moment of drama that Geminiani revealed much later.

As the riders entered their seventh hour of racing they agreed to stop for a change of clothes. It was seven o’clock in the morning, so was fully light, but when Anquetil stopped, he refused to ride any further. Geminiani had to step in, and because Anquetil was adamant it was over and just wanted to get into a car, he tried something drastic.

“I always knew what to say to Jacques no matter what he was going through, and I had a hunch about what it would take this time to snap him out of his intention. I told him I understood, I understood how he must feel, how hard he’d been pushed, and that disarmed him.

“So with his guard down I went in for the kill. I said: ‘Okay Jacques, I understand. I only ask one thing of you – shake my hand now, for it will be the last time I ever shake hands with you because I can’t stand losers.’

“Jacques glared at me, but in doing so I saw what I’d said had worked. The fight was back in his eyes, I could see it. He didn’t say anything, then he turned his head away and quietly changed into the dry clothes I had for him.

“He got back on his bike, still not saying a word, and started riding. From that moment I knew he would win, if only to spite me,” Geminiani recalled.

Right after Raphael Geminiani’s 7am ‘pep talk’

Right after Raphael Geminiani’s 7am ‘pep talk’

As the day warmed up Anquetil felt his strength returning. He began to launch attacks with Stablinski, each going one after the other, and soon only the great Tom Simpson was able to match them. But then they started on him, attacking in turn, causing Simpson to chase every time while the other followed.

Simpson had a problem, and he responded in the only way he knew – he attacked back.

Anquetil’s two team-mates took turns to chase him down, and this went on for kilometre after kilometre, until the breakaway was in the streets of Paris.

Anquetil and Stablinski discussing what to about Tom Simpson (just behind them)

Anquetil and Stablinski discussing what to about Tom Simpson (just behind them)

Then Anquetil threw everything into one effort. It was too much for Simpson, and Anquetil rode alone into the Parc des Princes stadium, where 20,000 spectators welcomed him.

Anquetil in the streets of Paris, flat out to victory in the Parc des Princes.

Anquetil in the streets of Paris, flat out to victory in the Parc des Princes.

The race was won. The impossible double had been achieved, and hearts were won too. For the first time in his life Jacques Anquetil received a wave of genuine warmth on his lap of honour around the velodrome.

The Parc des Princes crowd stood as one, applauding as he circled the track. But this time it wasn’t grudging admiration, it was spontaneous and heartfelt.

Victory lap in a packed Parc des Princes with Stablinski and the Derny.

Victory lap in a packed Parc des Princes with Stablinski and the Derny.

Geminiani was proved right – Raymond Poulidor could win the 1965 Tour de France and everyone would still be talking about Jacques Anquetil. And even that didn’t happen.

Poulidor underestimated a young Italian – Felice Gimondi, riding in his first Tour.

He gifted Gimondi too much of a lead, expecting him to crumble, which never happened. As time would later prove, Felice Gimondi was one of the best of his generation, and Raymond Poulidor had missed another shot at glory.

You can read more about this, and reveal the man behind the mask in Cycling Legends 03 Jacques Anquetil - available for pre-order now!

1 comment

Absolutely superb piece. Looking forward to reading the whole book.