Countdown!

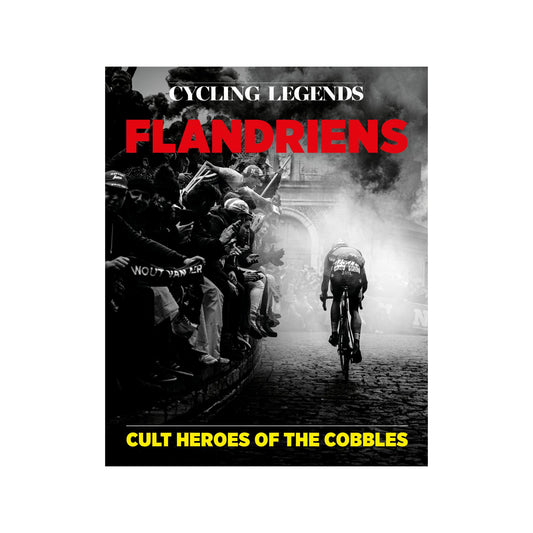

With 68 days to the first cobbled classic of 2025, Chris Sidwells looks at the history of Het Nieuwsblad, the race that changed its name but not its nature.

Let’s deal with the name change first – because it’s simple. Het Nieuwsblad was called Het Volk, and the change came because the first newspaper took over the second. How Het Volk started is a little more complicated and requires me to be Uncle Albert to your Del-boy. It happened during the war - well, slightly afterwards.

Flanders was a key battlefield through the First World War, Flemish people had their sights set on survival, not cycling. The Tour of Flanders, Ronde van Vlaanderen in Flemish, was created in 1913 by a sports journalist, Karel Van Wijnendaele and sponsored by the journal he worked for, Sportwereld. It couldn’t possibly be run.

Karel Van Wijnendaele, founder of the Tour of Flanders

It did though run through the Second World War, apart from 1940. Sportwereld continued its sponsorship and Van Wijnendaele organised it.

Nazi occupiers wanted life to be as normal as possible, so long as locals cooperated, life was allowed to go on as normally as possible.

However, once the war ended co-operation was seen as collaboration, and that caused a big problem for Sportwereld. It was one of several newspapers taken over by the Belgian government, and several of its journalists were convicted of collaboration.

Injustice

Van Wijnendaele wasn’t one of them, but he was banned from ever working as a journalist. The thing is he wasn’t a collaborator. In fact quite the opposite.

Love of cycling, and love of the race he created and had grown was why he ran the Tour of Flanders through the war. It definitely wasn’t sympathy for fascism.

Van Wijnendaele secretly worked for the allies, hiding British pilots in his house. Banning him from the job he loved was an injustice, but he had to seek help from the British to reverse it.

The help came in the form of a letter from Field Marshal Montgomery’s office, a letter that verified Van Wijnendaele’s heroic acts. He was back in the game, but straight into another fight.

Take over

As things settled down the Belgian government allowed Het Nieuwsblad to control Sportwereld, and with it the Tour of Flanders. Van Wijnendaele was hired by Het Nieuwsblad to write about cycling and to run the race, but now politics get involved in this story.

Het Nieuwsblad was politically conservative, and it had a rival Flemish newspaper, Het Volk (The People), which was founded in Ghent and controlled by Christian Labour organisations. Het Volk began promoting sports events in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, including in 1945 a new bike race for professionals called the Omloop van Vlaanderen.

But Omloop and Ronde have similar meanings in Flemish, so Het Nieuwsblad protested to the Belgian Cycling Federation, which insisted Het Volk change the name of its race to Omloop Het Volk.

Another famous Flemish race was born, and now, since Het Nieuwsblad and Het Volk merged in 2009, what was Omloop Het Volk is Omloop Het Nieuwsblad.

Did you follow all of that? Sorry to be a bit long-winded, but now you know the background we can get down to some of the riders who feature in the history of Het Volk/Het Nieuwsblad and helped make the race what it is today.

The Flying Milkman

Omloop Het Volk grew in importance throughout the 1950s. Then from 1957 to 1959 it linked with Ghent-Wevelgem to form the Flanders Trophy weekend. Ghent-Wevelgem was on the Saturday and Omloop Het Volk on Sunday. The Irish rider Shay Elliott won the last version of Het Volk in that format, he was also the first non-Belgian to win the race.

There have been many great winners of Het Nieuwsblad, but Frans Verbeek stands out, if only because he was a milkman when he won for the first time in 1970. It was at the start of Verbeek’s second pro career, when he was a very different rider to the one he’d been during his first.

Verbeek had turned pro in 1963 for the Flemish Wiel’s-Groene Leeuw team. He won the 1963 season-closing Putte-Kapellen race in Belgium, then in 1964 he won a version of the Tour of Flanders restricted to first year professionals. After that Verbeek started the 1964 Tour de France, and he did okay until stage nine, a 239-kilometre epic over the Cime de la Bonette, the highest through road in France.

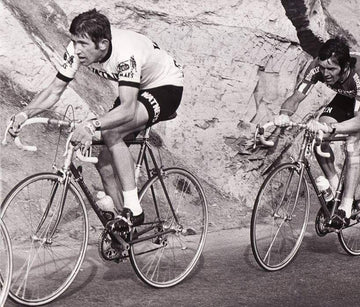

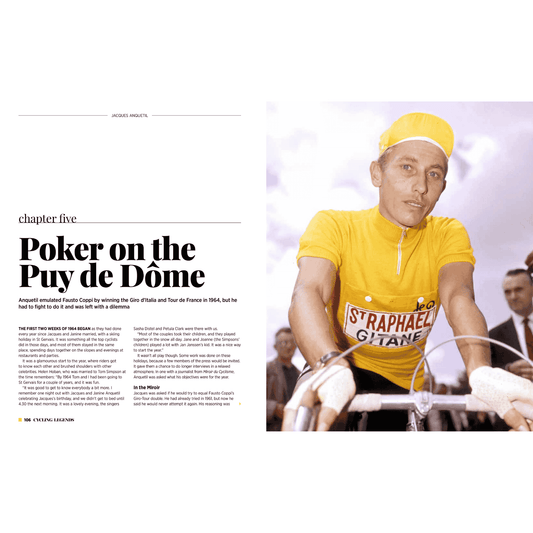

Jacques Anquetil won the stage, outsprinting Tom Simpson after seven and a half hour’s racing, but Verbeek abandoned somewhere on the road. He said years later that it was just too much suffering for the money he was making.

Poor pay

Sixties cycling was hard. The best, like Anquetil and Simpson were paid very well, but riders had to win big races to earn big money. Nobody paid for potential. “I didn’t want my wife to get a job, but despite winning some races and doing well in others I wasn’t earning enough to support us, so in 1966 I stopped. I took over a milk delivery round, we expanded it and I forgot all about racing,” he says.

Verbeek still followed the results, and in 1967 made an off-the-cuff remark about a race winner who was in the newspaper. “I was in my father’s bike shop, and I saw somebody I raced against had won quite a big race, so I just said, well if he can win that I could have won it.”

“But this guy in the shop overheard me. He was fan of mine when I raced so he said, “Well, why don’t you do it then?” So I decided to race again, but I wasn’t going to give up work to do it.”

“My father’s friend had a business that imported whisky, and he gave me a contract for six months from May 1968 and paid me 2500 Belgian francs per month (roughly £250 per month now). I still did my milk deliveries in the morning and I trained in the afternoon, and I did okay. I did the same the following year and I had six wins. I even delivered milk and cream to bakeries on the morning I won Het Volk for the first time in 1970,” he said.

Two in a row

That victory convinced Verbeek to give up the milk delivery business and go full-time pro. He started an almost manic training regime, one that saw him rest for only two weeks at the end of October, then start training up to eight hours a day.

He won Het Volk again in 1972, and many more races, even though he had to slug it out with the likes of Eddy Merckx. “My era was the easiest to race in, but the hardest to win. All the tactics you needed was follow Merckx, but beating him was another question,” Verbeek says.

On the subject of Eddy, he won Het Volk twice. Then in 1974 and 1975 Merckx’s super-domestique Joseph Bruyère won two in a row, setting a trend. Freddy Maertens won two in succession (1977 and ’78), then Alfons De Wolf (1982 and ’83), then Eddy Planckaert (1984 and ’85), then Wilfred Nelissen (1993 and ’94), and Peter Van Petegem in 1997 and ’98.

The first British winner of Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, the name changed in 2009, Ian Stannard did the double in 2014 and 2015. So did Greg Van Avermaet in 2016 and 2017, but there haven’t been any double winners since.

So at the moment the records of the three-time Het Volk/Nieuwsblad winners, Ernest Sterckx (1952, ’53 and ’56) Bruyère, who chalked up a third victory in 1980, and Van Petegem, who added the 2002 race to his tally, look safe.

Hope you enjoyed our little look at the history of the first cobbled classic of 2025, and hope you enjoy watching it. We can’t wait. Bring on the stones!