Today we’re going Italian, back to a long-gone race, a two-man team time trial classic that had some amazing winners.

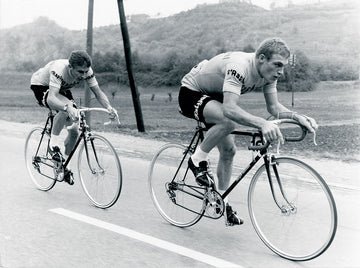

There’s something special about the glorious symbiosis of a team time trial. Success requires all individual time trials do, plus something extra. Power, concentration, calculation can be taken as read, but a team time trial also requires honesty, self-sacrifice and, perhaps most important, egos must be left in the start house.

Not that they always were, but that only that adds another layer to toe the Baracchi story. In fact we think they should bring it back. What about Mathieu van der Poel paired with Wout van Aert? Or Tadej Pogačar with Jonas Vingegaard? Would they gel, or would they just try to rip each other apart?

Celebrating grandad

The Trofeo Baracchi was created by Mino Baracchi, a rich Bergamo businessman who wanted a race to honour his grandfather, a true Tifosi. The first edition was an individual time trial for amateurs held in 1941. Then Mino heard about the format for a race that no longer existed, but dated back to 1917.

It was a two-man time trial for professionals, but not any professionals, only the best of their generation were invited. They were paid to appear, then paired up by the organisers, so they could end up riding with a deadly rival or a friend.

The race was called the Giro Della Provincia di Milano, and it ran from Milan to Como then back to Milan, where it finished on the Sempione track. The Sepmione was demolished in 1928, leaving Milan without a velodrome until the Vigorelli was built in 1935. But the race continued until 1937 when it was won by Frenchman Maurice Archambaud riding with an Italian, Aldo Bini.

War break

The Second World War stopped everything for a while, including Mimo Baracchi’s new race. But as things returned to normality afterwards, Mimo was determined to put back on again. He continued with the individual time trial format for five years, but in 1949 decided to copy the old Giro della Provincia di Milano.

He designed a testing 100-kilometre route of hills and flat roads around Bergamo, then paid the best racers to ride it. And just to attract more attention, he made the Trofeo Baracchi the last big pro race of the year.

The first two-man Baracchi winner in 1949 certainly attracted attention, it was the ‘Lion of Mugello’ Fiorenzo Magni. Magni had won one of his eventual three Giri d’Italia by then, and the first of his hat-trick in the Tour of Flanders. He won the 1949 Trofeo Baracchi with Adolfo Grosso, then won with different partners for the next two years. Magni had a penchant for hat-tricks.

Nino Defilippis from Turin won with Giancarlo Astrua in 1952, then it was Fausto Coppi’s turn. He won three times with Riccardo Filippi between 1953 and 1955. Then again in 1957 with Ercole Baldini.

By then the Trofeo Baracchi Trophy had found a classic course, Bergamo to Milan, with a finish on the hallowed boards of the Velodromo Vigorelli. That became the staple route through the rest of the race’s glory years.

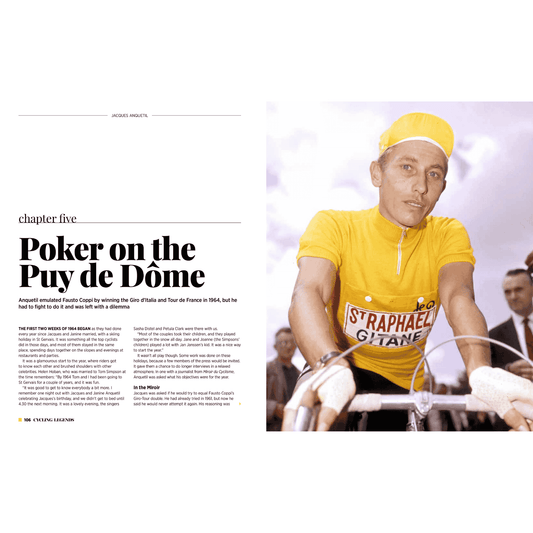

The humbling of Jacques

Jacques Anquetil was the master time triallist of his generation, one of the greatest of all time, but he hated the Trofeo Baracchi. He ‘only’ won it three times, the ‘only’ is added because he won the classic individual time trial of the day, the Grand Prix des Nations, and incredible nine times.

Anquetil could drive himself as hard as he needed, so long as he dictated the speed and the speed was constant. He had a computer for a brain that helped him spread his effort along any race route to the millimetre. But he didn’t like it when someone else set the pace in a time trial, especially if that pace was erratic. He didn’t like team time trails, they upset his rhythm.

In 1962 Anquetil rode the Trofeo Baracchi with his German St Raphael team mate, Rudi Altig. At that time Anquetil deeply distrusted Altig, and had connived several times within his own team to put him at a disadvantage.

Altig was great rider, a powerful man who started out as a track world champion, won classics, became road race world champion in 1966, and won the 1962 Vuelta. That last race was where Anquetil started having problems with him. Like so many of Anquetil’s problems it was something he created, and only existed in his mind.

As cyclists Anquetil and Altig couldn’t have been more different. Anquetil was all time trial, as smooth as silk and a steady as a diesel. Altig was all punch and power, capable of upping the pace in an instant, and he had a killer sprint.

Altig nearly killed the Frenchman in the 1962 Trofeo Baracchi. After Altig muscled through to do his turn at pace setting, upping it abruptly every time he did so, Anquetil was broken.

He wasn’t in good form anyway, was down on training and was just having one of those days any cyclist can have, ‘un jour sans’ (a day without) as the French call them. It was all Anquetil could do to hang on in behind Altig, then towards the end he couldn’t even do that and was dropped a couple of times.

Altig waited, but Anquetil was in such a bad way the German had to literally push him along the road to help him regain some vestige of strength. It was humiliating, and Anquetil added the experience to the sticker book of grudges he had with Altig.

Catwalk for talent

That was one of the most eventful editions of the Trofeo Baracchi, most of them were a straightforward catwalk for talent. Eddy Merckx won the race three times, Felice Gimondi won twice, but the King of the Baracchi is Francesco Moser with five victories between 1974 and 1985.

In fact it’s seven in total for the Moser family, because the oldest racing brother Aldo won twice. Sadly, though, even towards the end of Moser’s streak the Trofeo Baracchi had a much better past than its present. It involved setting aside time for some specific training, and the race calendar was becoming more and more crowded.

Bordeaux-Paris, a very different race but one that also needed a period of special training, died in 1988. The last two-man Trofeo Baracchi was run in 1990. They tried it solo for 1991, but that was it; the end. Tony Rominger is the last winner of the once fabulous Trofeo Baracchi.

1 comment

A fantastic history of this great race.