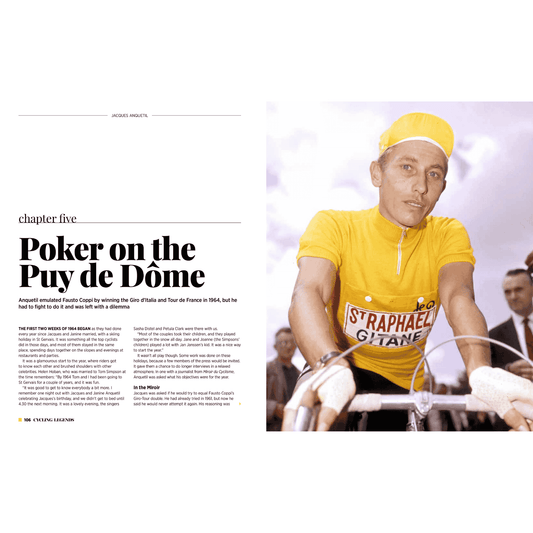

Three men have now achieved cycling’s Triple Crown. Eddy Merckx (1974), Stephen Roche (1987) and Tadej Pogačar (2024). Combining Grand Tour victory with single-day racing success at this level is so rare only five had ever done Tour de France – Worlds doubles before, the last was 35 years ago…

The big buzz leading up to the 1989 World Championships in Chambéry was all about Greg LeMond’s contract negotiations for 1990. LeMond had just made a remarkable comeback, winning the 1989 Tour de France after enduring both physical and emotional hardships. Following his historic 1986 Tour victory — the first by any American — LeMond was nearly killed in a shooting accident in 1987.

From hardly being able to get a contact at the start of 1989, everybody wanted LeMond for 1990. Several teams, including the deep pocketed 7-Eleven and Z squads, were bidding for him. LeMond was about to become the world’s first million dollar cyclist.

A good world championships would seal that, and he had a stellar one. LeMond dominated tactically, mentally and physically to join George Speicher (1933) Louison Bobet (1954), Eddy Merckx (1971 and 1974) and Stephen Roche (1987) in winning the Tour and the Worlds in the same year.

Italy was strong, all united behind Gianni Bugno. Dutchmen Steven Rooks and Gert-Jan Theunisse were in great form, and Belgium’s Claude Criquielion was determined to make up for the disappointment of 1988, when in the final dash for the title he crashed after a coming together with Canada’s Steve Bauer. Then despite their small teams, Sean Kelly and Russia’s Dimitri Konyshev couldn’t be discounted.

Fractious weather

Black clouds threatened the opening laps, during which the riders were buffeted by cold winds blowing off the Alps. The day’s first serious break contained Konyshev, Thierry Claveyrolat of France, Thomas Wegmuller from Switzerland and a Dutch rider, Marten Ducrot.

They built a significant lead, but it was never decisive - the weather was though. After 19 laps, and the race breaking up under constant attacks from behind, the heavens opened. Rooks was the first to catch the leaders, hammering up the circuit’s biggest climb, Montagnole, while rain hammered down on him. Then the storm.

Under white flashes of lighting and to the cymbal clashes of thunder, a strong group set off in pursuit of the leaders. They quickly caught Ducrot and Wegmuller, leaving three up front, but the real firepower was chasing.

Kelly was there with his team mate Martin Earley, Marino Lejaretta of Spain, Denmark’s Rolf Sorenson, Bugno, Fignon, LeMond and the warring duo of 12 months ago, Bauer and Criquielion.

Fantastic finale

They reached the front just before Montagnole was climbed for the final time. Fignon attacked, LeMond reacted, towing the others with him. Fignon had only lost the Tour by 8 seconds, and wanted revenge. LeMond knew he wouldn’t get it; “His attack looked good and he gained quickly on us, but the gap stayed as it was, so I knew I could close it,” the American said afterwards.

Fignon thought he knew better. Once caught he went again, and again LeMond seemed to be letting him get a gap, and when it failed to grow he closed it.

LeMond caught Fignon just before the top of the climb and blew right by. Fignon caught up on the slippery descent, so did Sean Kelly. Three were chasing three now, but the front three were no match.

With LeMond, Fignon and Kelly going full bore they shot past Claveyrolat and Rooks, but they didn’t lie down. Both made it back in varying degrees of desperation.

Six riders approached the one kilometre to go sign, and Fignon made one last desperate bid. LeMond didn’t hesitate this time. He sprinted after the Frenchman, towing Konyshev, Kelly and Rooks in his wake.

It took seconds to catch Fignon, who looked at LeMond and wagged a finger at him, as if he thought the American was racing just to make him lose instead of winning himself. He was wrong, and there was no time for more attacks.

Wrong gear

In the end it was simple. LeMond led out the sprint with 200 metres to go and nobody got past. After six-plus hours in the cold and rain, enduring storm and hail nobody had anything. Konyshev took second, and Sean Kelly resigned himself to third.

“I chose the wrong gearing for the sprint, 53 x 13 and knew I had lost well before the line. I stopped sprinting with 10 or 15 metres to go, there was no point,” Kelly said later. Kelly’s top gear certainly was no match for the 54 x 12 LeMond pushed, and the Irishman visibly eased once he’d made sure of a medal.

Greg LeMond wins an epic 1989 world championships. Konyshev (right, Soviet Union - silver), Kelly (left, Ireland - bronze).

LeMond’s face told the story as he crossed the finish line, his white teeth flashing in a determined grin. No one was as strong as LeMond that day, and unfortunately, he would never reach those heights again.

He won the Tour de France once more in 1990, but by then the lead pellets surgeons couldn’t remove—too close to his heart—had started to take their toll on him.

However, that 1989 Wagnerian worlds, and one of the greatest comebacks in sport will always belong to Greg LeMond.