King of six-day racing when six-day racing really mattered, Patrick Sercu talks about his team mate, rival and great friend, Eddy Merckx.

Words: Chris Sidwells

Photos: Cycling Legends Collection

Sadly Patrick Sercu is no longer with us, but I will never forget him for two reasons. First was his mastery of six-day racing, the winter sports of cycling that really mattered until the 1990s, when cycling fans began to lose interest.

I was lucky enough to witness Patrick racing in a couple of the later London Six-Days held on a temporary track inside the Empire Pool Wembley, and he was spectacular!

The other reason is much more personal. It comes from 2004, right when I was starting out as a cycling journalist. Patrick was kind enough to invite me to his home to have a long relaxed conversation with him, which became my debut interview published in Cycle Sport magazine.

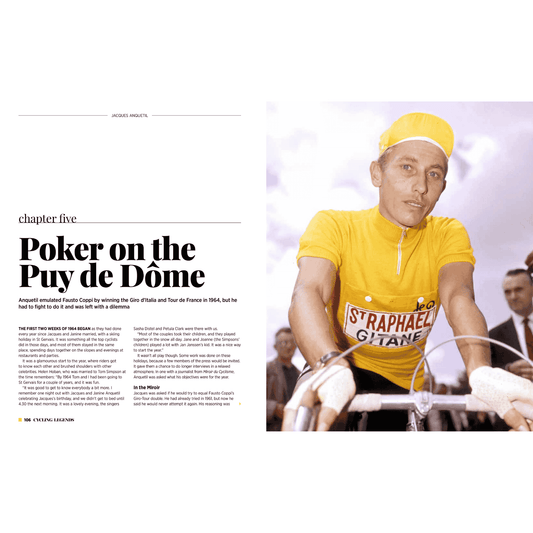

Patrick Sercu 1964 Olympic Champion jersey

During our chat he spoke about many things. About his own career, which had enormous range - from winning track sprint world titles and a gold medal in the 1000-metre time trial at the 1964 Olympics, to stage wins and the green jersey in the Tour de France.

He also spoke about his contemporary Eddy Merckx, about their similarities and differences, about their rivalry and friendship. And what came through was despite them ruling cycling, summer and winter, through the late sixties and early seventies, Sercu’s admiration was for Merckx while being modest about own achievements.

Patrick Sercu at the time of our interview

Different backgrounds

Patrick Sercu’s father is Albert Sercu, a successful but typically rugged Belgian pro cyclist with working-class roots. Eddy Merckx’s father was a grocer in a prosperous part of Brussels. A solid member of the middle-class bourgeoisie, while Albert Sercu came from and lived in rural West Flanders. Merckx is from the city, Sercu from the country.

“We had very different backgrounds,” Sercu confirmed. “When I visited Eddy’s home for the first time I thought how well-off his family was compared to us. We still became friends, although at first it was only because it was a good thing for us to do so. Eddy had built up a reputation on the road, and I had become a track sprinter, but literally by accident.

“What happened was I crashed in a road race in 1963, and my injuries prevented me from racing on the road for a while. If I couldn’t race I would have to go into the army - we still had conscription in Belgium back then.

“I had a good sprint at the end of a road race, so when my injuries healed a bit I trained on the track for four weeks, focussing on sprinting, and I won the 1963 amateur sprint world title. That kept me out of the army because the Olympics were the following year, and the Belgian team wanted me for the track.

“Then my father thought it would be good for me to ride Madison races with Eddy in winter track meetings. He suggested it to Merckx’s trainer, Felicien Vervaecke, who agreed. I had done Madisons with Romain de Loof, who was from West Flanders like me, but now I was with Eddy”

Merckx and Sercu complimented each other. Merckx was very strong and quite fast, and Sercu was very fast and quite strong. That’s perfect Madison pairing. They were successful from the start, racing on the Brussels indoor track during the winter of 1963/4.

MerckxSercu one of the greatest ever Madison teams

It was a marriage of convenience, two formidable forces joining together for their mutual benefit, but it took the cold of a Norwegian winter before they really bonded.

“We got closer when we were on a training camp in Norway. It was early in 1964 with the Belgian Olympic squad. It gave me the chance to get to know Eddy a lot better.

“We had quite a lot of time on our hands in between training, which was mostly cross-country skiing. We talked, but I watched him too. I saw how serious he was about anything he did, and I was the same.”

“Eddy worked hard at everything. He trained hard, and he rested hard. He was careful about what he ate. And when others went out for a drink, he stayed in his room like I did. It was the training camp that really brought us together. We found out that we thought the same way about cycling, the thing we’d both chosen to make our careers,” Sercu said.

Going pro

Merckx won his first world title, the amateur road race in Sallanches in 1964. The same year Sercu scored Olympic gold in Tokyo. They were hottest new kids on the block, and a lot of pro teams wanted them.

Sercu the track sprinter after winning the 1967 professional spring world title

They chose a Belgian one, Solo-Superia but didn’t really get together again much until the following winter, as Sercu explained:

“My world and Olympic titles meant I concentrated on the track for the first few years of my career, even in the summer when Eddy was road racing. We teamed up together in the winter of 1965 to ride our first professional six-day races.”

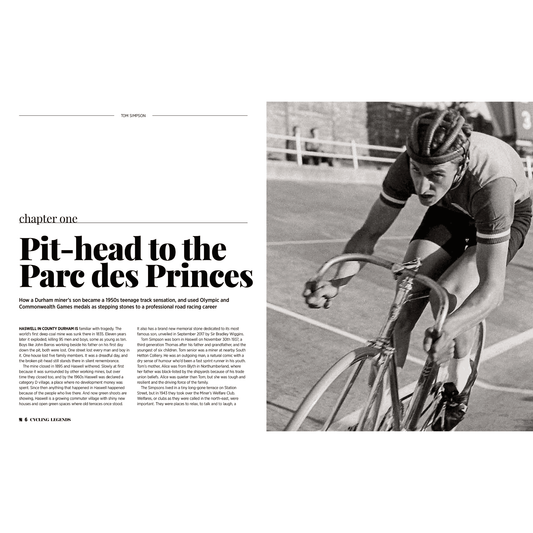

It didn’t take them long to win. Their first ever six-day was in Brussels, where they were narrowly beaten by 1965 pro road race world champion Tom Simpson, teamed with Dutchman Peter Post. The young Belgians quickly turned the tables.

The next six-day was in Ghent a few days later. The two teams fought head to head all week, and the matter as only settled in the final few laps of the final Madison.

It was a terrific race, with Sercu-Merckx just winning in a new record time of 58 minutes 4 seconds for 50 kilometres, a track record that stood for many years.

Favourite partner

Sercu-Merckx were one of the best Madison teams there’s ever been. The greatest road racer and greatest all-round track rider together in one unit. It was sometimes unbeatable. Merckx’s incredible strength was the perfect foil for Sercu’s lightning speed. Merckx was The Cannibal and they called Sercu the Flemish Arrow.

Patrick Sercu (right) with fellow West Flandrien and 1970 pros raod race world champion Jean Pierre Monsere, who died in an accident within months of this photo.

There are still some old fans in Ghent who remember the amazing night when Merckx-Sercu won the Belgian Madison title by an incredible nine laps.

Merckx was asked why they kept on lapping the field, and replied: “After three laps the crowd started shouting for more - ‘four’ they chanted, then ‘five,’ then ‘six’. I couldn’t resist that, I had to play to it,” he told reporters.

“Merckx was defiantly my favourite partner in the sixes. I rode with him 25 times in my six-day career and we won 17. That nearly 70 percent success,” Sercu pointed out.

The hurly burly of six-day racing. The Rotterdam Six with Peter Post relaying Sercu into the Madison fray.

Praise indeed from the man who still holds the record for six-day victories. He won 88 out of the 200 he took part in, but still wondered: “How many would I have won riding with Merckx every time?”

That wasn’t possible because Merckx had such hard road seasons, especially after winning the Tour de France in 1969. He still rode a few six-days though, and with Sercu he still won. Although Sercu pointed out: “Eddy would sometimes come to races a little out of form.”

Sercu (right) with Felice Gimondi in a Milan Six-Day.

Road ambitions

By 1969 Sercu was looking for success on the road himself. “My father won a classic, Het Volk in 1947 and I wanted to do the same. Eddy and I were in the same team, Faema in 1969, and I thought that staying there would bring us into conflict. We were very alike. We both wanted to be the best. So I left Eddy’s team, but it was a mistake. He was much more formidable as a rival,” Sercu said.

Merckx was indeed a formidable rival, even against an old friend. No favours could be done, it wasn’t in The Cannibal’s nature. Sercu found his friend’s attitude hard to live with, and admits it upset him at the time.

One occasion particularly narked him. He and Merckx were together in a break coming into the finish of Ghent-Wevelgem. Sercu was easily the fastest sprinter in the group, and wondered if Merckx would curb his ambition for once, letting the race end in a sprint. He didn’t.

Merckx attacked and won on his own. At the time Sercu said that he couldn’t understand why. Why with so many victories Merckx wouldn’t let one extra slip away to an old friend. But the much older Sercu I spoke to understood.

“His sense of honour would not let him give away a race. It would have dishonoured the race, and all those who had won it before him. That’s the way he thought. I respect him now for it, I was the same on the track, and looking back I never gave Merckx a victory there,” Sercu said.

No classic

Patrick Sercu never did win a classic. In retrospect he thought: “I had a six-hour limit. The distances of the classics were too great for me. Maybe it was because I spent my winters on the track spinning low gears and lacked a bit of power.

Sercu (right) trying to achieve his classic-winning ambition in a very wet Dwars door Vlaandren.

“Maybe with the team structures they have today I could have won one. With a team dedicated to getting a sprinter like me to the finish, maybe then I would have won one,” he said, then explained why that didn’t happen.

“Racing wasn’t structured like it is now. Teams didn’t have as much money, so riders had to sprint for places at the finish to win prize money. It was often better for a team to get fifth, sixth and seventh than one of their members win and nobody else place in the first ten,” he told me.

Friends reunited

Eventually Merckx and Sercu reunited in a team. “It was 1977 with Fiat, and I had my best year on the road. On the face of it that suggests it was a mistake to ride in a different team, but Eddy wasn’t himself that year, so it’s not that I won races because he let me. He wasn’t as strong anymore,” Sercu said.

Close to the end of our conversation I asked Patrick what he thought were Eddy Merckx’s greatest qualities?

“His strength of character, integrity and sense of duty. For example, I remember that in his last year of racing, even though physically he had some strength left, mentally he was empty for bike racing, but he still made all the arrangements for the team after a promised sponsor pulled out.

“He could have walked away, but his sense of duty made him see it through. It was the same with his bike factory. He gave some of his old team-mates jobs in it, and he worked through hard times as well as good, just to keep everything going for others,” Sercu said.

Sercu in green and Merckx in the yellow jersey of the Tour de France.

I hope you enjoyed this look at Eddy Merckx through the eyes of someone who knew him well for a very long time. Someone who grew up with him in a way.

It won’t be the only part of my conversation with Patrick Sercu, and with other great champions I’ll be sharing with you on cyclinglegends.co.uk. More soon!

8 comments

Great content

Thank you

Keep it up ✅

great read

Hi Chris

As usual, a really well researched and written article.

Cheers Nigel