New cyclists maybe don’t know Les West, a top British rider in the 1960s and ‘70s who raced mostly in the UK. Only two GB riders have ever finished higher in the men’s elite road race championships. This is his story.

Words: Chris Sidwells || Photos: Cycling Legends Collection

This was big, the biggest day for racing in the UK at the time; Eddy Merckx, the greatest road racer ever has the world’s cycling elite gasping in his wake on a little green hill in rural Leicestershire. It’s near the end of lap one of the 1970 world professional road race championships, and everybody who is anybody in professional racing is lined out behind the great Belgian.

Merckx was fresh from his second Tour de France and Giro d’Italia wins, his first Giro-Tour double, he won Paris-Roubaix in 1970 for good measure. And the Belgian team also had Roger De Vlaeminck, Walter Godefroot, Frans Verbeek and a super-talented 21 year-old called Jean-Pierre Monseré, who won Il Lombardia the previous year only days after turning pro.

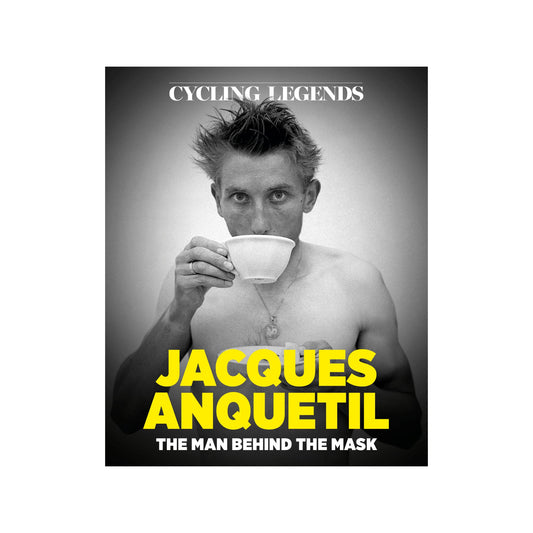

Italy had Felice Gimondi, one of the very few who could race toe to toe with Eddy Merckx and get a result, and Michelle Dancelli, lone winner of Milan-San Remo in 1970. France fielded a young team led by an old hand, Raymond Poulidor, and managed by his old rival Jacques Anquetil. The Dutch had 1968 Tour de France winner Jan Janssen and the defending world champion Harm Ottenbros. All the continentals brought their A game to this cool, cloudy, windy August Sunday in Leicestershire. The British team meant business too.

The Brits

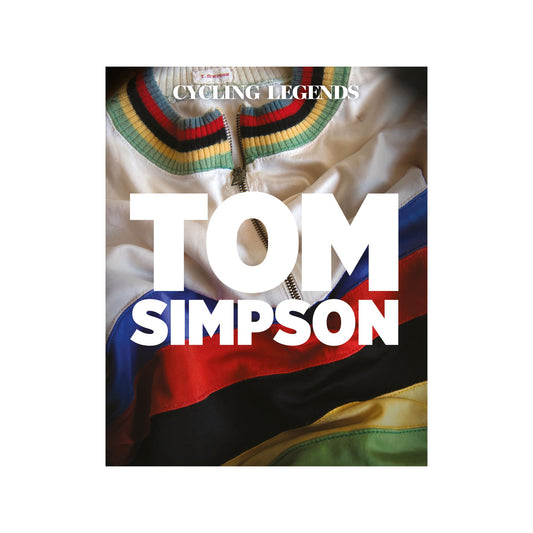

It was a mix of European and home-based riders. No obvious leader like it had in 1965 when they took on the world and helped Tom Simpson become the first ever British world pro road race champion, but talented riders who were determined to punch above their weight in the first home worlds.

It had been a good one too. The track championships held earlier in the month at Leicester’s Saffron Lane Velodrome saw Hugh Porter win gold, Ian Hallam take silver and Beryl Burton the bronze medal in the professional, amateur and women’s individual pursuits. There were other promising performances too.

Barry Hoban and Michael Wright had the experience at world level, both had won stages in the Tour de France, both lived in Belgium and rode for top French pro teams, but Hoban was coming back from broken ribs that stopped him in the 1970 Tour. Before the start he said, “I’m fit but not fit enough. I needed a week or two more to put and edge on my form.” The Brit-based pack had worked towards this race all year.

Two of the best rode for Holdsworth-Campagnolo. Colin Lewis, twice a Tour de France finisher won the last British pro race before the worlds, the Seward Brothers GP in South Wales, then did 400 miles training in the next four days, before tapering for today. The other Holdsworth rider was the mercurial Les West.

West was a wonder and a puzzle, on his day he was brilliant, but it had to be his day; he had to be up for it, and luckily he was on August 16th, 1970. He’d had a great amateur career, one of the best of his generation. He took the silver medal in the 1966 amateur world road race championships, which spiked interest from big pro teams, but due to an erroneous report in a newspaper the solid offer never came, but neither did West chase it.

This what he says happened; “The Bic team, who Jacques Anquetil rode for at the time, said they wanted me. Vin Denson was a Bic rider and told me I was in, but they never sent a contract. What happened was I’d raced in Holland in 1966. I came home after the worlds, but I found out later there’d been stories in the press over there saying I’d signed for the big Dutch pro team, Willem II. The people at Bic saw that, so they didn’t go through with the offer, and I didn’t push it. I could have done, but I just carried on racing as an amateur, the Olympic were coming up in 1968.”

West won Britain’s biggest and truly international stage race the Milk Race for a second time in 1967, but had an unfortunate Olympic Games in Mexico. He punctured early in the road race, had to wait ages for a wheel change, then had to make another bike change while chasing to get back on. He ended up minutes behind the main field, who were flying along on fresh legs. West continued alone for 30 miles but couldn’t catch them, so he stopped. There wasn’t really anything else he could do after that as an amateur, “So I turned pro, basically to do some different races,” he says.

He signed for Holdsworth-Campagnolo and stayed in their orange and kingfisher blue kit for the rest of his career, never chasing a continental career. He didn’t have the burning ambition of a Tom Simpson or a Barry Hoban. They moved heaven and earth to break into top level of pro cycling, uprooting their lives to live in Europe. They would have chased that Bic contract down, but it wasn’t in West’s nature. He was an incredible bike rider, but he didn’t have that desire. The 1970 world pro road race championships showed his class, though.

Circuit criticised

The race circuit had been criticised; it wasn’t hard enough for the pro worlds some said, but the undulating 15-kilometre loop covered 18 times for the 268-kilometre race, with help from a very stiff wind, delivered an aggressive race that went right down to the wire.

It didn’t start well for West. The early laps saw him taking pain at the back of the peloton, whiplashed by constant attacks at the front. Breaks were forming, getting caught, and others attacked immediately. It was impossible to move up, the pace was too high. The peloton was splitting behind him, it was only a matter of time before West would be the wrong end of a gap. Then there was a crash, and West got lucky.

“It was lined out and I’d dropped back a bit, then there was a crash just up ahead, which caused a split in front of me and suddenly the wind hit me and took my breath away. I was struggling, trying to close the gap, fighting for breath, but the gap got bigger and bigger. I thought, this is over, I was ready to give it up, then I went round a corner and everybody in front was sitting up and eating and drinking. I went straight to the front and stayed there, it’s easier there,” he explains.

Felice Gimondi

The Italians were active from early on, firing off riders from lap five until they had Michelle Dancelli, Gianni Motta, Giacinto Santambrogio and Felice Gimondi in a seven-man break with Alain Vasseur for France, Michael Wright and Belgium’s Jean-Pierre Monseré. They went for 110 kilometres and it was lap 15 before the rest reeled them in. But on the point of being caught Gimondi and Vasseur jumped away, and the French and Italian team put the brakes on behind.

Crunch time

It’s moments like this when races are won, and the other teams hesitated. On the little climb before Mallory Park motor racing circuit where the race finished and where the riders went through each lap, Jean-Pierre Monseré attacked. Frenchman Charly Rouxel went with him and so did Les West. A few minutes later the 1969 Danish world amateur road race champion Leif Mortensen bridged across to them, and together they caught Gimondi and Vasseur.

This was it, the winning break. “When I looked around at the other riders I thought, this is good they won’t know who I am; I’ll skive. But then Mortensen saw me, he was a new pro and we’d raced together as amateurs, so he said, “Come on West you must work”, so I had to go through,” West says.

With two laps to go the break had 1 minute and 10 seconds on the peloton, which was chasing but wasn’t gaining. British bike fans couldn’t believe it, they went crazy chanting “West West West,” louder than the “Forza Gimondi” cries of the Tifosi. Mallory Park erupted when West went though, and the progress of the break could be heard right around the circuit. It looked good, but Eddy Merckx hadn’t had his say yet.

Merckx’s response

He hit the climb before Mallory Park with all he’d got, then hurtled around the motor racing circuit with the peloton pinging to pieces behind him. With one lap to go Merckx had the lead down to 54 seconds, then his team mate Frans Verbeek started to help.

On and on Merckx went, with Verbeek doing turns when he could. The lead dropped to 45 seconds along the winding road to Newbold Verdon. Then with six to go Jan Janssen and the Dutch started, and the lead fell to under 30 seconds. That was too close for Monseré. He’d worked all year for this one, refusing to ride the Tour de France and riding Belgian Kermesses instead, training before and after them. It was the speed and miles system many Belgian world champions had used before him.

Monseré on the top step of the podium in Leicester

Monseré attacked on a tricky descent, but it was a test. Gimondi was the quickest to react, and the rest hauled themselves back up to the pair on the final climb. Monseré noted Gimondi was the strongest, he would make sure the Italian was nowhere near him when he attacked again.

They entered Mallory Park for the final time, two kilometres left, and Monseré went again. This was for real. He could sprint, nobody expected him to attack, so it caught the others by surprise. The Belgian went clear, the gap stuck for a bit then he started pulling away. Within 1500 metres he had enough to coast the last few hundred in front of delirious fans from his native West Flanders.

Gimondi tried to catch Monseré but he had nothing left, and Mortenson nipped around him for the silver medal. Gimondi took the bronze, and with Rouxel and Vasseur tailed off by Monseré’s move, Les West rolled across the line in fourth.

No medal but a wonderful achievement. Even today, with British riders winning the Tour de France, only two Brits have ever finished higher than West in what is now the men’s elite world road race championships; Tom Simpson when he won in 1965, and Mark Cavendish with his 2011 victory and 2016 second place. Simpson finished fourth twice and Ben Swift finished fifth in 2017, and that’s it. That’s all the British top-five finishers in the men’s elite road worlds in the 90 years since they began. That’s how good Les West was.

Footnote: Jean-Pierre ‘Jempi’ Monseré is still the second youngest world pro road race champion ever after his countryman Karel Kaers (1934). His brilliant life ended in March 1971, when an unauthorised motor vehicle got onto a race circuit in Belgium and hit him. A huge talent gone in seconds. Monseré’s tragic story will be a future Cycling Legends Big Read.

5 comments

Les West is my hero. He has been since he visited me in hospital in Hartshill in Stoke in 1967 to present me with my cycling proficiency badge. I’d been hit be a motorbike when I was running cross country. Les was presenting the cycling proficiency badges that year and I couldn’t attend. So with the help of my uncle (and auntie) who used to repair Les and Brian Rourke’s TT stop watches in his shop opposite Roy Swinnerton’s, Les came to see me. It thrilled me and it still does to this day. Thank you Les.

Les was pure class on a bike.

Les was one of the most talented British road racers ever. See the short 2016 film on YouTube “Milk Race On and On” for more about him.

I was at Mallory Park that day.

There is a photo somewhere of West “rolling in” and not sprinting. Would a Hoban or Simpson have pushed harder for a medal? Who knows but this was one of the great British rides of all time.