After witnessing Geraint Thomas’s Tour de France debut in 2007, Chris Sidwells knew he had to find out more. This is what happened.

Words: Chris Sidwells || Photos: Andy Jones & Chris Sidwells.

Thomas was living in Quaratta in Tuscany at the time, and on the face of it his final 2007 Tour de France placing of 140th might not shout future winner, but there was something about the way he rode that stood out.

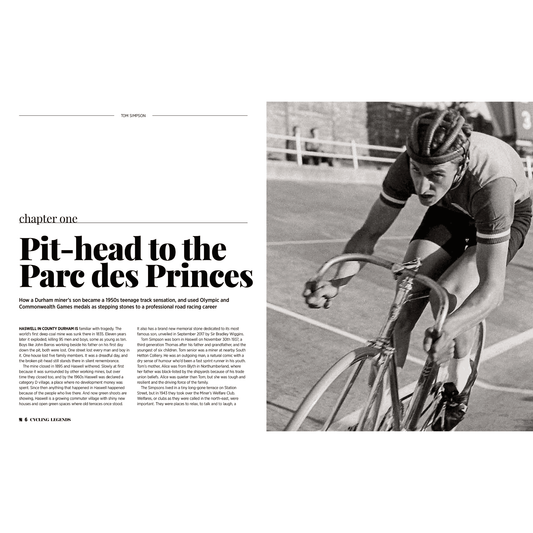

He was 21, easily the youngest rider, and his focus was four minutes of intense effort on the track, not 90-odd hours flogging around the roads of France. But whenever we grabbed a few post-stage words from him, no matter what he’d been through, he recovered so quickly he looked like he’d ridden to the shops and back.

Even though he might have just done 200-plus kilometres over five mountains in 30-degree heat, he seemed to soak it up. No matter what the race threw at him, nothing left a mark. It’s easy to say in hindsight, but I really did think there was a lot more to Geraint Thomas than four minutes of intense effort in a velodrome.

Academy grad

He had a week’s rest after the race, then had some shorter stage-races, so I arranged to meet him in Quaratta about a month after the Tour. British Cycling’s under-23 academy had its summer base there, and although Thomas left the academy when he turned pro, having other British riders around convinced him to stay in the area.

When I poled up at Thomas’s apartment another academy graduate, Mark Cavendish, was visiting with Max Sciandri who looked after the Brits in Italy then. It was almost a home from home, a colony of Brits bang in the middle of Italy’s cycling heartland. Except the weather was better.

“It’s great for training, the weather is good and you’ve got mountains right on the doorstep,” Thomas explained. Then said: “When I’m at home in Cardiff I have to ride for about ninety minutes before I get to a good climb.

“Plus everyone knows you here, and they are interested in cycling so they are interested in you. When it was announced that I was going to the Tour de France the locals got really excited. And I like the atmosphere here. I like the culture where you can come out and have a coffee and just sit outside a café and talk.”

Doppio Espresso

So that’s what we did, we sat down for pre-ride espresso at a café in Quaratta’s main square. I’d gone to Italy to get photos of him riding his favourite training route for one of the ‘Ride With’ features Cycling Weekly magazine did then, but it was this longer interview I was really after.

I started by asking Geraint where he felt home was, Cardiff or Quaratta? “Here, I’m going to buy a house in Manchester first, but I want to buy one here as well. I think Cav does too, and maybe Steve Cummings,” he said.

Thomas needed a place in Manchester because he was a mainstay of British Cycling’s Olympic track squad. The Tour de France might have opened his eyes to his potential as a road rider, but the track was where he saw his immediate future. The next thing he said, though, was prescient.

Following Brad

“I sort of see myself following what Brad Wiggins has done. I see myself as a track rider first. My big ambition next year is for the Olympics in the team pursuit. Then I’ll focus on the road for a couple of years, then it’s the Olympics in London. That’s what Brad is doing at the moment.”

Now I’m a bit old fashioned, and I the road is the pinnacle of cycling. Thomas eventually thought the same, as he underlined 11 years later when he won the race; “It’s the Tour de France, man!” But at 21 the Tour was just an intense three-week block of endurance prep for the track. I asked him if he achieved his ambition of a gold medal in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing, which he did, would he pursue a career on the road.

“Not yet, I really want to ride the Olympics in Britain and the track is my best option. The team pursuit would be first again, but maybe I could take on the Madison by then. I would love to ride the Madison in London with Cav,” he explained.

Never shirk the work

But if I’ve made it look like Geraint Thomas was just breezing through cycling in 2007, he wasn’t. He never underestimated the work he needed to do to maintain his place in the British team pursuit four, neither did he shirk any. “There are seven or eight riders who could step into our team pursuit. It isn’t a production line. A lot of people think you just rock up and join the plan, and next thing you are world champion. It doesn’t work like that, a lot of hard work and commitment goes into it from everybody,” he said.

British cycling success was still something of a novelty in 2007, and most of it was on the track, although there were the green shoots of a road revival. In the early years of lottery funding BC’s performance planners spent their money on the track because the odds were better on getting a return, but they always believed that the endurance track talent they were nurturing would eventually flower on the road.

As Shane Sutton explained to me at the time: “The pursuit is an endurance event. If a guy can generate 500 watts, spinning a massive gear at 100-plus rpm for 4 minutes, the physiology is there to climb mountains and perform on the road. It’s just the training, focus and preparation that needs to change.”

Words into action

And 2007 was the year when BC began to turn Sutton’s words into action. Cavendish and Thomas, the first graduates of BC’s lottery-funded performance plan took on the Tour de France and other top level road races. Cavendish, for example, won the Scheldeprijs, then stages in both the Four days of Dunkirk and Volta a Catalunya, and had two top-tens in Tour de France stages before pulling out on stage eight.

They also experienced how big top level road racing was, and it left an impression. “Me and Cav have known each other for years and grew up through the academy. It was an amazing experience to be at the start of the first stage of the Tour this year in the centre of London. We were stood next to each other with big smiles on our faces, both taking it in. It was an incredible feeling,” Thomas told me.

I asked him what other impressions of the world’s biggest bike race, the race he eventually won, had made on him during that first encounter. “It was fantastic, an amazing experience. I didn’t think it would affect me like it did, but when I caught my first sight of the Eifel Tower on the last day, that was special. I will never forget it. I was riding next to David Millar when I saw the tower.

“I really got caught up in the atmosphere that day. We had to chase a breakaway, and I was on the front going up the Champs-Élysées. That was the best experience. And then there was the view when you came out of the tunnel each lap,” Thomas said.

But there were tough times to endure before that good one in Paris. “I knew I would struggle to finish, but I was never going to get off. I was always going to try and get to the end. The first bad day was the stage to Tignes. I was dropped early, and spent 100 kilometres chasing on my own. Eventually I caught the grupetto. I knew there were two long climbs and the grupetto would take them steadily, so I just stuck at it. I was really proud of that.”

Self-discovery

Thomas discovered things about himself during his first Tour, hidden strengths. “I found out how to hurt myself,” he told me. “Looking back, every day at some point I was on the limit. And on stages 10 and 11 I was on the limit all day. It was very hot, and I have never suffered as much as I did then. Getting through was a big boost for my morale though. I was proud to do it, and I was surprised that I didn’t feel so bad in the last week.

“The first couple of races afterwards were disappointing. I developed a bit of a chest infection, but I felt the difference finishing the Tour has made to me physically during the Tour of Burgos. It’s a tough race, but right through I felt strong. I wasn’t flying, but I could just ride and ride. That’s what guys who had done the Tour told me I would feel.

“I also noticed the difference in my head. Where before I’d be thinking, ‘right this is a five day race’, now I’m thinking this is only a five day race. Before I’d be, ‘right there are three climbs today’. Now I’m saying there’s only three climbs today, and they’re only 300 metres.

“Brad told me it would be like that after the Tour. I spoke to him a lot, we had plenty of time to talk on some of those 20-kilometre climbs, and he said that four kilometres would never seem the same to me after the Tour.

“I was also amazed how big a deal the Tour was, how I had two or three journalists wanting to talk to me before every stage, and two or three after. I don’t think it all sank in until I was back with my friends in Cardiff, away from the Tour. Then I thought to myself - that was a big month I’ve just had.”

What did he do on his week off in Cardiff? “I had a few beers, and a few more besides. I did a lot of sleeping too. It was really nice to be normal for a week”

The future

Despite his big track ambitions, with quite few good pro races, including the Tour de France, in his legs in 2007, Thomas was starting to get a picture of where his abilities might take him on the road. “I think one day I might be able to go for the same kind of races and stages that Filippo Pozzato goes for. I think I can be a rider like him, who can get over the climbs, not the biggest ones maybe, and still be there at the end,” he said.

Then I asked him what the biggest lesson he’d learned from his first year as a pro road racer was. “The thing about being a pro is that you have to go to a race for the team. In the GB team it’s all about you, about what’s best for you. You ride this race or that race just because that is part of your build up. As a pro you ride races for your pro team, and you have to do your job according to the team’s objective.”

Thomas left a big impression on the 2007 Tour de France. The quiet dignified way in which he fought through to Paris impressed people. And the Tour left a big impression on Thomas. Even though without any family background in the sport he didn’t enter cycling all starry-eyed about the Tour de France, I got the feeling that doing well on the road, especially in the Tour de France, was becoming a thing for him. A possibility he hadn’t considered until then.

The Olympics and the team pursuit were still what he was committed to in 2007. A gold medal, something he’d dreamt about since he was kid in Cardiff trying out as a swimmer and finding cycling by accident, was within his grasp.

That flying feeling

What’s more, he loved the speed of track racing. His eyes lit up when he talked about the Tour de France sprint finishes he’d just experienced, and they did the same when he talked about the speed of the British team pursuit squad.

“It feels incredible, there’s nothing like whapping around a track at 60-plus kph with everybody so close. When we do our flying kilos in training and Ed Clancy kicks in at the front, it feels amazing,” he said.

I asked him what qualities do good team pursuiter riders have. “Well it’s very technical,” he replied. “You’ve got to get the changes perfect every time, and you’ve got to ride smoothly and dead close to the wheel in front. It takes a lot of practice. I‘ve done a lot of track racing over the years, riding scratch and points races, and it all helps you to follow a wheel and move around the track.”

Thomas’s team mate Chris Newton once said that the team pursuit is like doing four flat out sprints with no recovery in between, and Thomas agreed. “Yeah, it’s flat out but it’s smooth. It’s difficult to describe how you do it. The first two turns are critical, they are full on, but you can’t overdo it. The last two are sprinting, but still controlled. It’s a real fine line between being fast enough and overdoing it.”

And how are the skills perfected, I asked? “Practice. With the academy we did drill after drill after drill, and always at race speed. It becomes second nature after a while, but it takes hours and hours to get there.”

My final question was something Thomas referred to during the 2018 Tour de France when asked how he was coping with the pressure of leading the race. Had being a team pursuiter helped in his debut at the top level of road racing?

“I think the biggest help it’s been is in dealing with the pressure. There is no pressure like sitting with three of your mates waiting to go up before a team pursuit final. That’s intense,” he replied.

In 2018 he reiterated what he said when we met in Quaratta by saying; “Wearing the yellow jersey is nowhere near as nerve-wracking as waiting at the start of an Olympic final.”

Track racing helps a road racer in many ways, but more than anything its binary, you get it right or wrong, and that helps track trained road racers deliver under pressure. Geraint Thomas certainly did deliver Geraint, and we thank him for it.