Chris has a look at what pro riders of yesteryear did in the off-season and finds that, except the very best, they worked; and we mean they worked at other jobs.

Being a pro cyclists is a full-on round-the-year job now. The World Tour starts in January in Australia, moves through the middle-east, then into Europe for the big races of each spring, summer, and autumn.

The calendar is full, but nobody rides all the big races now. In fact pros race less than they ever did, but they train much more. They train all year too, but they didn’t years ago, they couldn’t, many of them didn’t get paid through the winter. And those who did needed to do some racing to keep some cash flowing.

There were still bills to pay, and even as recently as the 1980s a 12 month contract from a team wasn’t a given. There was no minimum wage either, and some riders, even those who’d ridden the Tour de France, weren’t paid at all.

They got expenses, free kit, performance bonuses and a share of any prize money their team won. For a while there was even a team for unemployed French pros called Amis du Tour de France that was sponsored by their equivalent of the DWP.

Most of the guys racing like this needed jobs in the winter. Some of them were what you’d expect a cyclist to do. Some simply returned to the family business, like the first British Tour de France stage winner, who went back to building between seasons. And one or two jobs were quite unusual.

The flying postman

The Breton rider André Le Dissez always worked in the winter, and he was a very good rider, a pro from 1957 until 1965 who ended his career with the Mercier-BP team.

He rode some big races, and won some too, including a stage of the 1959 Tour de France. But every winter Le Dissez worked as a postman in his home town of Plougenven. It was so well known in cycling that Le Dissez was nicknamed Le Factuer, the French word for postman, by riders and fans.

Others did all sorts of casual jobs - lorry driving was popular, so was labouring on farms or building sites. Many worked in their local bike shop, which was good for trade because employing the local pro attracted customers in for a chat, and hopefully they’d buy something.

Snow patrol

But perhaps the most interesting winter job held by a pro belonged to Robert Poulot from Arrens in the Midi-Pyrenees. Poulot was a pro for three years and he won only one race, the 1964 Tour des Combrailles, which doesn’t exist anymore. But he was also an excellent skier.

So good that he was recruited by the ski section of the French Customs Department, and spent every winter patrolling the high Pyrenees looking for smugglers. This was years before the Schengen agreement created a borderless Europe and long before the single currency, so the cost of goods, especially luxury goods varied between countries.

Smuggling to avoid tax and benefit from favourable exchange rates was a lucrative business. Poulot had worked for French Customs before he turned pro, so it was a simple thing for him to return to border control each winter. He even went back to full-time when his short pro career ended.

Farmer Foucher

Well into the 1970s and ‘80s many French pros came from farming backgrounds, and one really good one never gave up his farm, winter or summer.

André Foucher’s farm was in the Mayenne, which is where the Pays-de-Loire meets Brittany. He loved cycling from the day he got his first race bike at 15, but he always saw it as a hobby and a way of earning a bit of extra cash. Even when he was a Tour de France top ten finisher.

Foucher won lots of races as an amateur, fitting training around his farm work. He was so successful he took out an independent licence, which meant he could race against amateurs and pros and earn more money. Then in 1958 Foucher won the French national road race title for independents, and everyone wanted him to turn pro.

At first Foucher said no, explaining: “I have my work, I have my farm. Cycling isn’t a job it’s a recreation.” But he carried on winning, and pro teams carried on upping their offer.

Making hay

It got so much that Foucher had to take the offers seriously, and he turned pro in 1961 for Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune, but with one proviso. “They let me start my season later than everyone else, because I couldn’t do many races until we’d made the hay in late spring,” he told me when we met a few years ago at a race in Brittany.

He rode the Tour de France in his first year, but he was 28 by then. He won the Midi Libre stage race in 1964, and he finished sixth in the 1964 Tour de France, ending his pro career in 1967.

He carried on racing, though, eventually stopping in 1999 when he was 69. “I raced with a category in France called Hors Categorie, which was for ex-professionals, then I raced with the amateurs. I even trained with the Madiot brothers, Marc and Yvon, who come from the Mayenne, when I was in my fifties,” he told me.

Winter sports

So that’s what riders further down the packing order did in winter, basically the jobs they’d done before or anything they could get, but what did the top guys do in winter?

Fausto Coppi and his great rival Gino Bartali were both keen hunters, but Coppi being a marginal gains sort of guy never stopped thinking about cycling. To make the most of long treks through the hills with his gun, Coppi wore a weighted vest to get some resistance training while doing it.

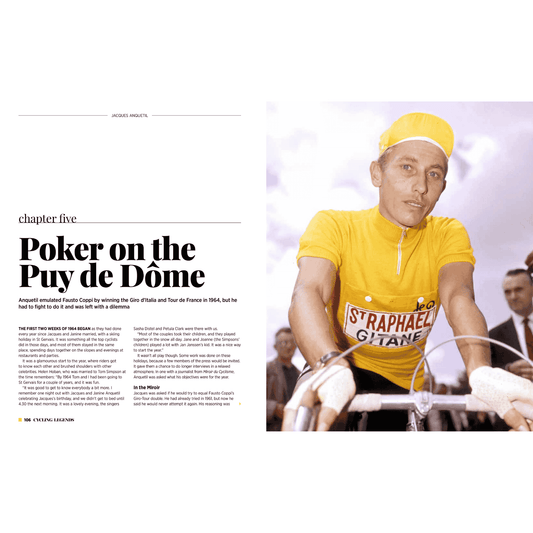

Winter sports were popular. Many top cyclists either could ski or they learned. Jacques Anquetil was an avid skier, and for a while there was even a pro rider’s ski championships at St Gervais each winter. But as time went on, and sports science developed, cyclists took up a different form of skiing. Some of them took it very seriously too.

Cross country

Some athletes started training at altitude in the 1970s and ‘80s for benefits they could derive in improving oxygen uptake and delivery. There wasn’t much time for cyclists to train at altitude during the busy racing season, so they went in the winter, and they went cross country skiing.

Cross-country skiing, skating and cycling have things in common, especially the way leg and back muscles are used in each of the sports. History is littered with skaters and skiers who became good cyclists, two of the most famous being brother and sister, Eric and Beth Heiden. Eric won five speed-skating gold medals at the 1980 Winter Olympics and went on to ride the Tour de France. His sister Beth won a speed-skating bronze medal at the same Olympics, while later in 1980 she won cycling’s world road race title. Beth was also an accomplished cross-country skier.

But by far the best skater/skier/cyclist is the 1980 Tour de France winner, Joop Zoetemelk. He was a Dutch regional speed skating champion before he started cycling in 1964, and his ability and familiarity with skates transferred quickly to skis.

His British Gan-Mercier team mate in the 1970s, Barry Hoban remembers it well. “We did ski training camps on the Plateau de Glieres in the French Alps, it was where the French national cross-country ski team used to train. We’d go out and do a lap or two of the prepared pistes, so about ten or so kilometres, and we’d get a good sweat going. But Joop would go off with the French ski team and do 50 kilometres or more. I’ve even known him ski 100 kilometres in a day,” Hoban says.

Winter racing

Of course some pros just carried on racing. The 1947 Tour de France winner Jean Robic won the first ever cyclo-cross world title in 1950. He carried on racing summer and winter until he was 40.

Rolf Wolfsohl of Germany won three men’s elite cyclo-cross world titles (1960, 1961 & 1963) and the 1965 Vuelta a Espana. He won other big road races too, and was a constant contender.

Roger De Vlaeminck, one of the greatest-ever classics riders, rode cyclo-cross every winter. He was men’s elite cyclo-cross world champion in 1975, the same year as he finished second in the world road race championships.

But Robic, Wolfsohl and Roger De Vlaeminck are special. Pascal Richard too, because he was cyclo-cross world champion in 1988, then won Liège-Bastogne-Liège and Olympic road gold medal in 1996. But not all road pros who did cyclo-cross in the winter were good at it.

Cross Madisons

Raymond Poulidor reckoned a bit of cyclo-cross was good training for the cobbled classics. Jacques Anquetil did the odd cross race too, and so did Eddy Merckx, Francesco Moser and many other top riders. But the events they took part in were more often exhibition races; cyclo-cross Madisons, where each road rider was paired with a good cyclo-cross man. Races like that were a big draw, so the riders got well paid for doing them, and the promoters charged people to watch.

Giuseppe Saronni was also a regular in these races, although he was a good cyclo-cross rider, and his brother, Antonio was a four-time Italian cyclo-cross champion. Claudio Chiappucci was another top road rider who could ride a good ‘cross. Chiappucchi was in the Italian team for the 1992 world championships in Leeds, where he chugged around the course at the back of the field to a wave of cheers and applause from the crowd.

Six-day races

But the place to see top road pros racing in the winter was in the velodromes of the six-day circuit. Top road racers were a big draw in the six-days, ensuring full houses night after night. That gave them real earning power; most top road riders did some of the six-days, and a few did them all, although they did compromise their potential on the road by doing so.

Road racers were usually paired with the best six-day regulars, so you got teams like Eddy Merckx and Patrick Sercu who won almost every time they rode together.

One-off winter track meetings were another big attraction, either to celebrate something in history, such as the annual Armistice Day meeting in Ghent, or there would be one-off omniums, many of which were billed as revenge matches. They might pit the first three riders in that year’s Tour de France against each other, or were inter-nation challenge matches, Belgium versus France and Belgium against the Netherlands were regulars.

Winds of change

So when did all this change, when did the need to get a job, go on ski camps or racing winter and summer become no longer necessary for the world’s top road riders?

Money did it from the mid-1980s onwards. As bigger sponsors were attracted to cycling they had more money. Bigger sponsors wanted results in big road races, so riders had to work harder at their winter training to ensure summer results. They were earning more money, so they could afford to focus on their main job – cycling.

Frans Verbeek of Belgium started training right through the winter in the 1970s, and slowly more and more followed him. But the biggest change came in the 1980s through one man, Greg LeMond.

When he became the first American to win the Tour de France in 1986 the race began to receive a lot more attention throughout the world. What had been a European sport became global. Pro cycling suddenly had a wider market for its sponsors. On top of that LeMond had a different attitude to contract negotiations.

He wanted to do the sport he loved, the sport he had such talent and aptitude for, but he wanted to be paid his worth by a team, not just paid enough. With his American lawyer he negotiated the first million dollar team contact with team sponsors La Vie Claire. Then did even better with the Z team in 1990, after his miraculous return from near death after a shooting accident.

But LeMond didn’t just raise the level of his pay, he raised it for all the riders he wanted in his teams. Slowly that spread across the whole of top-level men’s racing, and the main source of every pro rider’s income shifted.

They were paid more and more by their teams, so they were less dependent on race winnings and appearance contracts. They didn’t need to race summer and winter, didn’t need other jobs. They could focus on their one job, being the best pro road racer they could be.

1 comment

He taught cycling how to be like the modern politician! Once you could only serve your constituency for

a limited amount of time. Then, go back to the plow. So policy was made by the “working classes”. Now like in government and cycling, rules and races are dictated by career, wealthy, professionals! Thanks for nothing Greg!