Stage 14 of the 2025 Tour de France finishes in Superbagnères, a place the race doesn’t visit often, but when it does it’s always an epic.

Words: Chris Sidwells || Photos: Cycling Legends Collection

Superbagnères is a one-way climb to a ski station perched on a shelf above a cliff that towers over Bagnères-de-Luchon, and smack in the middle of the Pyrenees.

The mountain peaks around it are some the highest of the whole range, and the huge weight of 3000 metres of rock squeezes the earth below, heating it to produce thermal springs that are why Bagnères-de-Luchon was created in Roman times.

The town carries its history lightly, a French Harrogate with older folk there for the skiing or the spa, and young ones for snowboarding, climbing and night life. Bagnères-de-Luchon is sedate with a buzz - spas next to night clubs, five star hotels next to self-catering apartments, and there are cyclists all over the place.

Bagnères-de-Luchon sits at the bottom of the Col de Peyresourde and Portillon climbs, as well as Superbagnères. Plus it’s not far from the start of the Col de Menté, where Luis Ocana crashed out of the 1971 Tour while wearing the yellow jersey. It’s a cycling town.

Great Scott

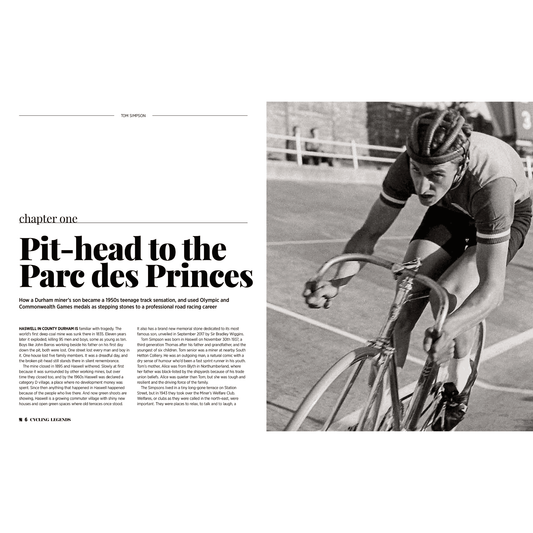

The first time the Tour de France climbed to Superbagnères was in 1961, when a Scotsman, Ken Laidlaw was first on its slopes. He was caught by the top, but Pippa York had revenge for Scotland when she won the stage that finished there in 1989.

The climb wasn’t used before 1961 because there was no road up it until then. The only transport to top was one of those scary-looking ratchet railways. But the new road created one of the most testing climbs in cycling at the time.

The first four kilometres, apart from a little dig at two kilometres, are quite easy and drastically reduce the overall gradient. After that the gradient increases, but at six kilometres in the climb becomes truly Pyrenean. The gradient varies from steep to very steep, but is never one or the other for very long.

Spectacular canyon

The tough bit starts at the Pont de Ravi, a bridge over a spectacular canyon called the Gouffre Richard. At this point the road also switches valleys from following the Pique to the Lys.

View down the Lys valley from the climb to Superbagnères

Four hairpin bends lead to a forest of pines called the Bois de Soulan. The trees are thick at first but the landscape becomes more scrubby and open near the top. Hairpin after hairpin leads there, and to a spectacular viewing point at 16 kilometres. The depth and scale of the valley and surrounding peaks can be appreciated for the first time.

Launch pad

This is where Greg LeMond caught his team mate Bernard Hinault in 1986. He rode on to win a stage that had been an absolute fire fight, because Hinault attacked on the descent of the Tourmalet, powered over the Aspin and Peyresourde alone and began the climb to Superbagnères that way too. But he was tiring.

Bernard Hinault on the rampage in the 1986 Tour

Once he caught Hinault, realising this was the key moment of the Tour, LeMond attacked to win the stage, his first and only mountain-top Tour stage victory.

A lot has been written about the 1986 Tour, and this stage in particular. Was Hinault trying to win, or was he just softening up the opposition for LeMond, as he claims? I think he was trying to make a point.

The point being that he had agreed to support LeMond in 1986 in exchange for LeMond’s help in the 1985 Tour after Hinault crashed near the finish in St Etienne. And Hinault attacked on the 1986 Superbagnères stage because he wanted to show that he could have won that Tour if he’d wanted to.

Greg LeMond and Andy Hampsten caught Hinault on the road up to Superbagnères

There’s a picture in Miroir du Cyclisme’s Tour special that year. It shows Hinault on the Peyresourde. A fan is holding up three fingers, presumably indicating that Hinault was three minutes ahead, and Hinault is looking straight at him. He raises a fist triumphantly, his face contorted into an expression that is part anger and part pure enjoyment. It’s like he’s saying to his public, “Hell yes, I could win this if I wanted. I’m still number one.”

But then there’s another in the same magazine taken after Hinault had been caught and dropped on Superbagnères. He’s on his own, and he mops his brow with the back of his hand. It’s a close up headshot that fills an entire page. Hinault’s eyes are shut, his head is down and his mouth open. So maybe I’m wrong. Whatever, it brought the best out in LeMond, and we are still talking about it.

Grand Hotel

The gradient lessens for a while then goes back to nine percent for the last pull to the summit, where the resort is dominated by a huge edifice called the Grand Hotel. It was built in 1922, contains 100 rooms and looks like someone lifted a hotel from the centre of Paris and dumped it on top of a mountain.

The hotel witnessed something in 1961 that the central Pyrenees is famous for. It had been a hot day, but clouds built up and hot became oppressive as the riders climbed to Superbagnères.

Five minutes before the first rider was due at the summit and apocalyptic thunderstorm broke out. The veteran Tour writer JB Wadley said in his report that it: “Rained, it hailed, thundered, the lightning struck, but above all a wind rushed around the mountain side, carrying all before it.”

Out of that confusion the Italian, Imerio Massignan emerged just ahead of the yellow jersey group to take the stage by eight seconds. Massignan isn’t so well known now, but he was probably the best climber in the world in 1961.

He had a skinny, ghost-like physique, tall with improbably long spindly arms and legs. He was so strange looking that his knick-name was The Spider of the Dolomites. It was Massignan’s only Tour de France stage win, although he won the 1960 and 1961 King of the Mountains titles.

Final thought

So that’s a brief description and some about the climb of Superbagnères to whet your appetite for next year’s Tour de France stage, but before I end this I want to reflect on how far British cycling has come from then.

Ken Laidlaw’s 1961 attack on Superbagnères might have been futile in the sense of any affect it had on the race, but it was crucial for his team. The 1961 Tour was contested by national teams and 12 riders started for the Great Britain squad, but by the Pyrenees it was down to three, and they were just about hanging on.

The two established riders in the team, Brian Robinson and Shay Elliott were both part of the pro peloton in Europe, both had places in what would now be WorldTour teams, but they weren’t riding as well as expected. Laidlaw had been talking about leaving the race the evening before, he was so tired.

The team’s morale was very low, but Laidlaw’s brave attack won him the £95 prize for being the most aggressive rider on the stage. That was not an insignificant amount in 1961, especially in the light of the team’s total winnings by the end of the Tour were £488 split three ways.

From £54 a week, to British riders winning Tour's 51 years later and now regularly competing shows just how far it's come.