A top classics rider, Eddy Planckaert retired in 1991. He was around for a while then disappeared, leaving only rumours. In 2006 Chris Sidwells tried to make contact, and this is what happened.

Words: Chris Sidwells

Photos: Luc Claessen, Presse Sports and Cycling Legends Media

‘Eddy Planckaert lives in a tepee in the woods,’ that was the rumour in cycling in the mid-2000s. Planckaert was as tough as any competitor when he raced, but his soul and spirit were different. Living with Native Americans, experimenting with transcendental meditation and out-of-body experiences were two of many things he wanted to try when he stopped racing. Living in the woods in a tepee - yeah, that sounded Eddy to me.

I was intrigued, finding him, finding out if it was true and talking to him would be interesting. He was always interesting, he still is, and I’ll leave what he’s doing today until the end.

Actually it didn’t take long to find him, because we had a mutual friend - Albert Beurick, who owned a cafe in Ghent. His name will be very familiar to any Brits who raced in Belgium between the 1950s and the ‘90s.

Albert, who sadly is no longer with us, knew everything and everybody in Flemish cycling, so I called him: “Sure, I know where he is. I can’t tell you where, and I can’t describe how to get there, but I can take you,” he told me. So one dull day in February 2006 I picked Albert up at the Café Den Houd in Ghent, and off we went. And eventually we found him.

Deep in the Forest

Eddy Planckaert was living deep in the Ardennes, and he did have a tepee. After Albert and I navigated the steep stony track to where he lived with his big boisterous family in a log cabin, Eddy told me: “The tepee is only for summer, and it’s not summer now.

It certainly wasn’t, there was thin covering of snow on the ground, but the cabin was warm and welcoming. It was by no means luxurious, but it was the only place he and his family could afford back then.

Not that he ever put much store in money. Life was to be lived in the moment and enjoyed, that was and I bet it still is Eddy Planckaert’s cornerstone belief.

He genuinely looked like he was enjoying the experience, even though he’d lost all of the money he’d made winning the Tour de France green jersey, Paris-Roubaix, Tour of Flanders and many other big races. How that happened is a long story, which over the next couple hours he told me in full. But first a bit of background.

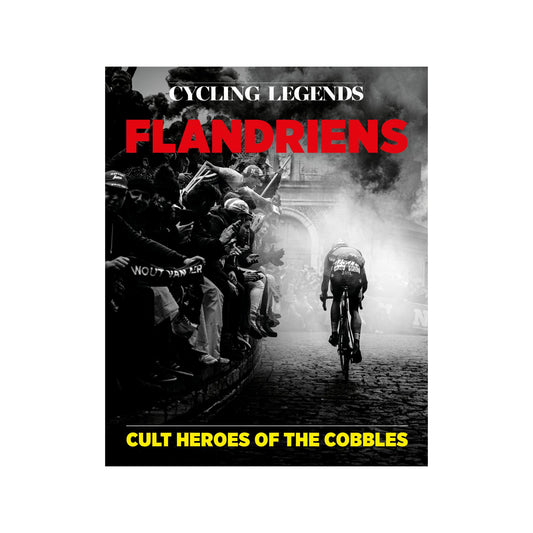

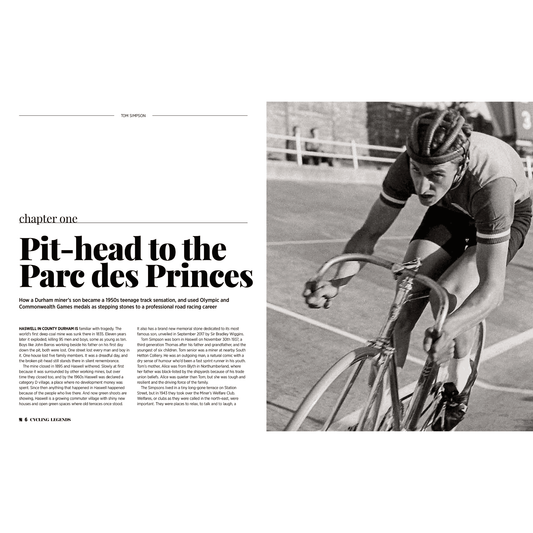

Eddy Plackaert - A king of the cobbles

Youngest brother

Eddy Planckaert is the youngest of three brothers, who are a Belgian cycling dynasty. They are sons of a Flemish farmer, very strong, and all very successful.

The eldest, Willy blazed the family trail into professional cycling after scoring a record number of race wins in one season with the amateurs. He continued winning with the pros, taking the green jersey in the 1966 Tour de France and he raced until he was well into his forties.

Brothers Walter (left) and Willy Planckaert

Walter was next, a fierce-looking granite slab of a bike racer with a gentle heart. He won the Tour of Flanders in 1976 and went on to be a respected sports director.

Then there was Eddy, “From the day I first opened my eyes all I saw was bikes,” he told me. He was the best of the Planckaerts, with the best results.

Willy’s son Jo, and Eddy’s son Francesco were both pro racers, but neither were as successful as their dads.

Haunting images

Eddy’s other childhood memory comes from pain and death - the death of his father. “It was the start of my life. I remember everything after that but little before it,” he told me, before adding: “I am still haunted by the image of my father lying injured at the scene of a car crash.”

Only minutes before the family were celebrating, the accident happened while travelling home from watching Willy Planckaert win another race. It was a shattering experience.

His father hung on, hospitalised for a year, but he couldn’t be saved. A photograph in Eddy’s autobiography De Helse Tocht (The Hell Tour) shows him standing uncomprehending, knee-high to the rest of his family. They are looking down at the broken, bed-ridden man, but Eddy is looking at the camera, his expression seems to be asking why. He’s been asking why ever since.

Questions

“It was a terrible thing to see your father hurt like that. It opened my eyes and made me wonder about the fairness of things, about whether there’s a God for example. If there is, with all the pain in the world we will fight the day I see him, I promise that,” he said.

After their father’s death, the eldest brother Willy took over as head of the family and Eddy became very close to his mother: “A truly beautiful woman who was left at 45 years old with no man, no money, but she never let us go without,” he recalled.

Another person the teenage Planckaert bonded with was a rival, not a Belgian but a young man of his own age who travelled from the other side of the world to race in Europe.

“I won everything as an amateur, it was easy,” Planckaert said. “I would hit the front and the opposition disappeared. Then one day I attacked as normal, moved over to see what damage I’d done behind, and this kid I’d never seen before flew past growling at me - it was Allan Peiper.

“I thought; what’s this? I’d never seen aggression like it. After that day we attacked together in every race. I still won because I was a better sprinter. Then one day I said to Allan: “You must win a race, I will give you the next victory.” And he said; “No you won’t. If I win, I win – I beat you. But don’t give me anything.” I’d never known anyone like him, so prickly, so good and so honest.

“We became very friendly after that. One day I went to the place where Allan was staying in Ghent, and it was terrible. The worst house I’ve ever been in. I couldn’t have lived there, so I asked my mum if Allan could stay with us. Of course she said yes. Allan moved in with me, sharing my room. We became closer than brothers. We believe the same way. Allan can be anywhere in the world now, but I feel him here next to me.”

Stand-out win

Eddy quickly found his feet as a pro. He was fast and strong, ideally suited to the classics, and given his Flemish roots you might be surprised what he said when I asked him which of his victories stands out the most?

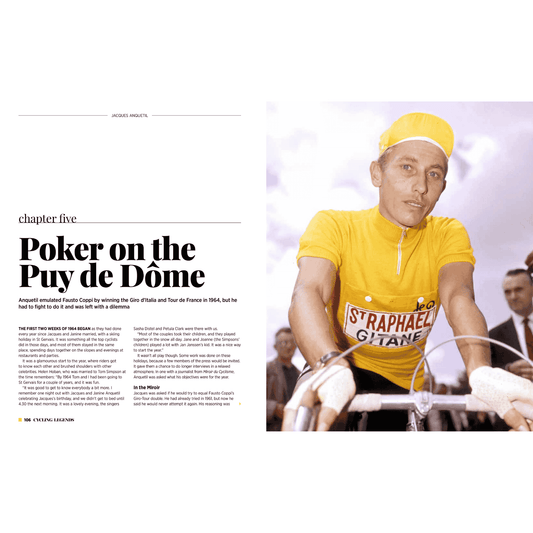

Close victory in Paris Roubaix 1990

“Every victory is beautiful,” he told me. “Paris-Roubaix is an obvious choice, but I’m proudest of my green jersey in the Tour de France. That was emotional for two reasons.

“First, my brother won the green jersey, I can remember him wearing it. That made it special, but what is even more incredible is the feeling you get from standing on the Champs-Elysées wearing one of the jerseys from the greatest race on earth. There you are, only a little bike racer and the whole of Paris is stopped for you. You feel like you own the Champs-Elysées that day. It’s incredible.”

Eddy's favourite victory - the Green Jersey in the 1988 Tour de France

Were there any races he felt he could have won but didn’t? “Yes, Milan-San Remo. With my abilities I should have won that. If I hadn’t been forced to stop in 1991 after I injured my back and it sapped my power, I’m sure I would have won it.”

Looking back, which of his teams did he like the best? “For organisation and giving you every opportunity to win it was Panasonic,” was Planckaert’s predictable answer, but he has too much soul to leave it there.

“The best feeling I ever had in a team, though, was with ADR. The spirit in that team was incredible. The manager, José de Cauwer created a team that was like a family. We felt like a family. And our results were amazing. I won the Tour of Flanders, Dirk Demol won Paris-Roubaix, and then there was Greg LeMond.”

Indeed there was. In 1989 the ADR team, a collection of Flemish riders brought together by the promise of big money, a promise not delivered to most, gave Greg LeMond a lifeline when he was struggling to get fit after recovering from gunshot wounds.

No other team was there for him, and LeMond repaid ADR with victory in the Tour de France and the World Championships, which was huge. LeMond also made a huge impression on Planckaert.

“He was so strong; amazing because he was so fragile. I remember in the 1989 Tour, in the team time trial, Greg was going so hard I couldn’t take my turn. I was one of the best in the team time trial with Panasonic, which was the best-ever in team time trials in my opinion. I could always take my turn with them, but this time I had to let Greg ride for two kilometres before I could go through,” Planckaert told me.

Eddy in is his favourite team - ADR.

Life outside cycling

Physical strength was something the Planckaert family held in high esteem. Everything the brothers did, everything they ate was to build strength for their cycling careers, but physical strength isn’t as much use once cycling has gone. In a bike race you can use your strength to batter the opposition. Planckaert found life away from racing can be a lot more complicated, and much harsher.

He always had a reputation for being unconventional, which in the conservative world of cycling is not difficult, although even the most free-thinking would acknowledge that some of Eddy Planckaert thoughts and hopes were pretty out there.

But studying the ways of Native Americans and Eastern mystics, as well as practising yoga in the hope of an out-of-body experience actually helped him cope with what had happened in the years following his retirement from racing.

When I visited Planckaert in 2006, despite all the races he won and the money he earned doing it, all the training and all his strength, he was flat broke. He admitted the experience nearly broke him.

“I thought about suicide, I even planned the way I would do it,” Planckaert told me. “I was going to take a chain and padlock myself to a pier in the sea when the tide was out. Then I would throw away the key and wait for the water to return.

“I could have done it too, for myself. You are a prisoner in this world and I think that death is a release, but I have a family and I could not leave them. That would be the moment though, wouldn’t it? Not when you lock the padlock, but when you throw away the key, then you will learn something, eh?”

Focus on the good

Thinking about and planning to take his own life is a terrible thing to go through, but Planckaert got through that, and through what happened to him, by focussing in what was good.

When we met he was truly happy living with his extraordinary family with nature all around them. There was no running water and no electricity but it didn’t seem to matter, and he was able to speak freely without bitterness about what happened to him.

“After I stopped racing I wanted to go into the mountains and concentrate on my meditation. I wanted peace, but what I wanted was a lot to ask of my wife, so I bought a farm in Belgium to be close to nature. The problem for me is you must have a steel heart to be a good farmer, and it wasn’t much of a challenge.”

That last statement might seem a bit strange until you know that Planckaert did not want to stop racing, his back stopped him racing. He tried to come back, but he couldn’t. He did an interview when he was running his farm, and he told the journalist that he really missed the struggle of bike racing.

Lithuania

Then out of the blue he announced he’d bought a saw-mill in Lithuania. With that, whether intentionally or not, he had his struggle. In those days even the most experienced, hard-bitten businessmen were wary of doing business behind the old Iron Curtain. A romantic like Planckaert was certain to have problems, but even he couldn’t have guessed at their extent.

“Working against the old Soviet apathy meant it was a constant fight to motivate the people in my factory. But I loved the place, I improved it, I spent thousands on buildings and machinery. We also bought a small log cabin in the woods. It was so quiet, only the forests and nature - deer, elk and wolves to keep you company. For a while I had everything, my struggle and my peace,” he told me.

But without Planckaert knowing it, things were going wrong. “I found two people I trusted to help me. It seemed to go well at first, but behind my back they were cutting me out in a very professional way. In the end I had responsibility for all the factory’s debts, but I couldn’t touch its profits. They stole it from me.

“I could have fought them, but there are two laws in Lithuania - the one you find in the courts, and the one you find at the wrong end of a gun. I was threatened, and I was scared for my life and the lives of my family. I had to come home to Belgium, and without income I couldn’t pay my debts, so I had to go bankrupt. That’s where I am now.”

Planckaert wasn’t bitter, just very matter-of-fact about it all, accepting even. I asked if it make him angry being robbed like that. “It did, but now I have discovered happiness, I have discovered I don’t need money. I had money and losing it made me sad. But now I am happy and I have none, so I see how pointless money is.

“People run around for money and power, they do terrible things to each other. Money brings out the beast in us. Money made the white man rob the Native Americans, money makes babies starve because of a cent on a barrel of oil. Money turns us into beasts. I have no money and I am happier now than ever I was. Everything I have now is real.”

Sequel

That was a good place to leave this part of the interview, although Eddy told me a lot more about cycling, which I will share with you on the coming months, one way or another. But I don’t want to leave this story here, because it’s only fair to tell you what happened to Eddy Planckaert and his family since that day.

First of all they were discovered by TV. Not long after I did this interview a TV producer visited Eddy and his family at the place where we found him. From that visit a TV series was born.

It was called De Planckaerts, and it was about Eddy having various adventures set against a backdrop of him and his family living their lives. It became very popular in Belgium, making personalities out of all of them. It also earned them some good money in the process, so today they are okay.

Very good money in fact, because today the Planckaerts live in a château and have a new TV series. It’s called Chateâu Planckaert, which we believed is aired each week on Sundays around lunchtime. But with or without money you can bank on Eddy Planckaert always being happy.

4 comments

A good story and nice to know that close finish in Paris – Roubaix was not a fluke. Steve Bauer was beaten by a great cyclist

Great write up, but your dates/years are probably not correct. Mid 2000’s/2006 tv series De Planckaerts had already been aired for years. First episode in 2003. I know because I was commissioning editor at broadcaster VTM at that moment. So I assume your visit at Eddy’s place happened in 2002.

Great story with a “happy ending”! Lol! I wonder if Eddy regrets telling of his disdain for money, or even the spotlight! Lol!

Fascinating story