The story of an extraordinary British race with an extraordinary British winner.

Words: Chris Sidwells & Barry Hoban ||

Photos: John Pierce Photosport International

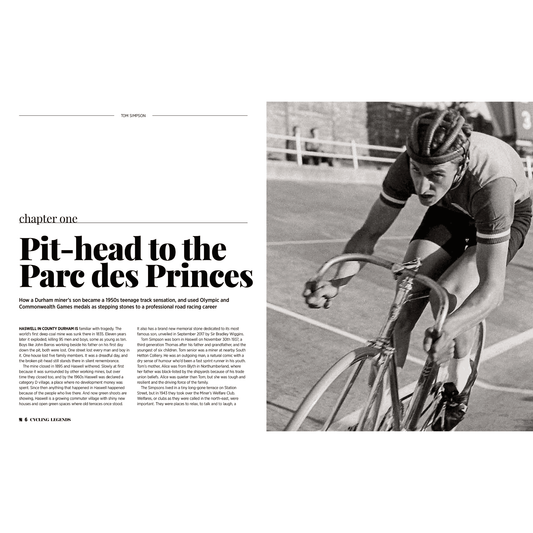

Rain lashes the bleak Pennine moors, dark clouds smother the tops, but through it one determined bike racer emerges, pounding up the long climb from Lancashire into Yorkshire, back-lit by following cars.

Barry Hoban is owning this race, a remarkable Marathon he took charge of early and never let go. Soon he’ll reach the top of the climb then plunge down into Yorkshire to win the 1979 London-Bradford race. A battle-hardened veteran taking his last big victory in his home county.

London-Bradford was a 260-mile single-day race. It replaced another epic, the 265-mile London-Holyhead, an important race for the band of pro riders who were based and raced in UK at the time.

Empire Stores sponsored the final two editions of London-Holyhead in 1977 and ‘78, but since Empire Stores was based in Bradford the organisers thought it would be a good idea to switch the finish to Bradford for 1979. The sponsor upped its money, and that’s where Hoban came in.

Hoban wasn’t based in the UK. He went to France in 1962, turned professional there in 1964 and in the coming years won eight Tour de France stages, two in the Vuelta, Ghent-Wevelgem and a bucketful of other good races. He was still racing in a top French pro team 15 years after making his pro debut, even though he was 39 by then. Which is exactly why the London-Bradford organisers wanted him in their race.

Good money

“Whenever UK race organisers had good money from a sponsor they wanted some continental riders to add a bit of colour to their race, which was fine but it caused friction between me and the British-based pros. The continentals were better prepared because we had longer and harder races, so more often than not the continentals won. The British pros felt like every time they had a good pay-day, we came over and took it from them,” Hoban says.

That’s what happened with London-Bradford in 1979. “One of the organisers, Stan Kite, and I don’t know what would have happened to British pro racing back then if it hadn’t been for Stan, rang me up and asked me if I’d ride the race and bring some continental riders with me.

“An ex-rider, Julien Stevens lived near us in Belgium and he was running a team called Boule d’Or-Lanoo, so I asked if he wanted to bring some of his guys over. I told him Stan would pay our expenses.

“I was winding down in 1979 really. I rode for the Miko-Mercier team, but I was 39 and it was my last year. There’d been a coup in the team, and the directeur sportif I had my best years with, Louis Caput, was thrown out and a recently retired rider, Jean-Pierre Danguillame, who I didn’t get along with was installed as the new director.

“I knew with Danguillaume I wouldn’t get selected for the Tour de France because we didn’t get along, so I’d been riding on my own in Belgium, where Julien Stevens looked after me in races, giving me a wheel if I punctured, or whatever.

“Anyway, I’d got a lot of high quality races in my legs and I was going well. The prize list of London to Bradford was good; 10 primes of £150 each in the towns along the way, and £1000 for the winner. That was good money in 1979, so I psyched myself up for it.

“This was going to be an objective, and I had the advantage over the British pros with the races I’d done. Riding in Belgium without a team meant I could ride 200 kilometre races on two bottles and what food I carried in my pockets.

“I always told new pros that they had to regard a 200-kilometre race like they used to ride 100 or 120-kilometre races. They had to be comfortable doing it day in day out, and with very little food. I was conditioned to that, and that’s a big advantage in an extra-long race like London to Bradford. So I was really up for it,” Hoban says.

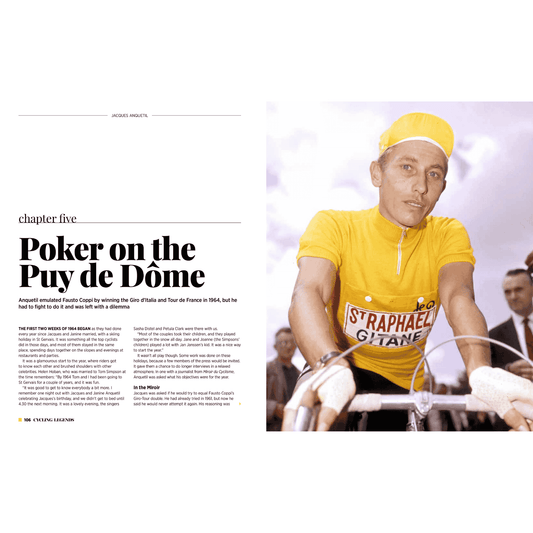

Barry Hoban (left) congratulated by world champion Tom Simpson on winning the 1966 Henninger Turm Classic.

Hampstead start

The race started outside the Post House Hotel in Hampstead, but was neutralised as far as Elstree, then it headed up the A5, just like London-Holyhead did.

Not much happened at the front in the early stages, it was just a matter of getting the miles done. There was more action at the back, with punctures and riders removing arm and leg warmers as the day warmed up.

The first cash prime was just before the 100-mile mark, and in a statement of intent Hoban won it by out-sprinting two British-based pros, Trevor Bull and Geoff Wiles.

Then he got in a short-lived breakaway, but it was jumped on by the Brits, who brought it back. Ian Banbury edged out Hoban for the next prime, then it got very frisky for the next 50 miles with attack after attack. But nothing stuck until one of the Boule d’Or Belgians, Benny Van de Auwere slipped off up the road.

That suited Hoban, Van Der Auware’s team mates sat back and handed the British pros a fait accompli - ride while we sit in, or you lose. The Brits rode and they limited Van Der Auware’s lead, but it cost them energy.

It also cost them money, because while he led the Belgian mopped four consecutive primes, netting £600 for the team’s kitty. There was only 50 miles left when Van Der Auware was finally caught. This was Hoban’s cue.

Out of Lancashire

“Coming into Oldham I knew we were approaching the critical climb, the one that goes from Lancashire into Yorkshire on the A62. I knew it from my early days. I knew it was long, and I knew you could make a real difference on it, especially if you hit the descent hard as well.

“I also knew that Ian Greenhalgh was local to Oldham, and when he attacked shortly before the town I waited for a couple of minutes then went after him,” Hoban says.

He quickly caught Greenhalgh, while the Belgians disappeared from the front of the peloton, leaving only the British pros to chase. When the road started going upwards after Oldham, Hoban pressed a bit harder on the pedals, dropped Greenhalgh and was away.

“He powered up the bleak, rain-soaked moorland climb to the top of Standedge, where a huge crowd of club riders were waiting. They gave Hoban a hero’s welcome as he crossed into Yorkshire.

On home road with just a few miles to go.

He kept the pressure on down the descent, and by the time he reached Marsden, which is only two and a half miles after the summit, Hoban was four minutes clear of a disintegrating bunch.

He’d gained that in the space of 12 miles, and it wasn’t because the rest had given up. Strong riders, Bill Nickson, Sid Barras, Paul Carbutt and Keith Lambert were chasing hard, but they made no impression. Hoban just kept pulling away.

“He took the prime in Huddersfield to thunderous applause, then headed for Leeds. There was 25 miles to go and Hoban had six minutes over his nearest rival.

Lumpy last bit

“The last bit was lumpy, and I remember at the top of one drag Julien Stevens, who was driving his team car behind me, came alongside and said, “You are winning this in an armchair.” But it wasn’t because the rest gave up, it was splitting to smithereens behind me. They were riding,” Hoban recalls.

But he was now riding roads he trained on almost every day as a young amateur. At one point the race passed within five miles of where Hoban was born. He even knew the track finish at Odsal Stadium in Bradford, where 8000 people welcomed him. “It was an odd-shaped track, the bankings weren’t equal, and it was pear-shaped if I remember,” Hoban told me.

Emotional moment

It was emotional moment, winning a big race in Yorkshire, the place he left 17 years before to live and race in France, but Hoban didn’t think about that until he was inside the stadium. “It never registered until I got near the finish. It was getting colder all the time with the rain, so I had plenty to think about,” he says.

Hoban won by six minutes and 53 seconds from Paul Carbutt and Bill Nickson. The indefatigable Benny Van Der Auwera was fourth a further minute behind. Bradford boy Dudley Hayton was fifth at 8 minutes 28 seconds, and Sid Barras was sixth, over nine minutes behind Barry Hoban.

Of the ten intermediate prizes Van Der Auwera won four, Hoban won three and Boule d’Or’s Eddy Van Haerens won one. “It was a good pay-day,” Hoban confirms.

It was total domination too. Hoban was a class act, and if anybody had doubted it they couldn’t after that rainy day in May.

Publishers note:

Vas-y-Barry, published by Cycling Legends Media, and now in its second edition due to demand, is Barry Hoban’s autobiography. It’s the second one he’s written, but when he talks about Vas-y-Barry, Hoban always says: “This is the one I really wanted to write after I stopped racing,”.

Vas-y-Barry is available to buy here.

2 comments

I remember it well. Also very fond memories seeing Barry riding the Vaux Gold Tankard along with Van Impe in the 60s.

What a race!